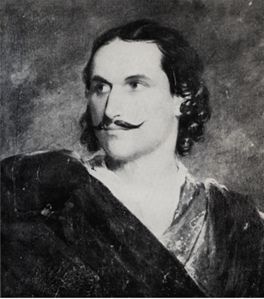

The Massacre at Paris 1792, a tendentious English take on the matter (for source of image see link)

Well is it with the king who keepeth a tight hold on the reins of his passion, restraineth his anger and preferreth justice and fairness to injustice and tyranny.

(Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh – page 65)

On the run-in to Christmas during this difficult time in terms of the current context of political uncertainty and division, it seemed a good idea to republish one of my longest sequence of posts ever, which focuses on the power of art.

As I indicated towards the end of the last post, as my reading of Richard Holmes’s 700 page account of Shelley’s life moved forward, though I lost none of my reservations about the man, they became balanced both by examples of his capacity for kindness at times and by the increasing depth and accessibility of his poetry.

I was also powerfully struck by how relevant his challenges and concerns still are to our world today. We also, as he was, are living in a country which watches terror abroad afraid that it will come to haunt us at home. Even though the desire for liberty had inspired the French Revolution, by the time the Jacobins gained power ruthless oppression had betrayed its original ideals, a pattern that Shelley, for reasons we’ll explore soon, became aware would tend to repeat itself. We have seen many of those repetitions take place across the world since his day, most conspicuously, but by no means only, in Stalin’s Russia and Mao’s China.

As I explained last time, I will be starting with a helicopter survey of Shelley’s life. Next week I’ll be looking at some ideas about the life/art relationship in general before taking a closer look at Shelley’s poetry prior to attempting to formulate a model of creativity from the wreckage.

Early Influences

In childhood, it would seem, Shelley ruled the roost (page 3):

Bysshe, the favourite of the servants, and secure in his position as tribal chief, ran riot at Field Place [his childhood home].

His time at boarding school was a torment but he had two factors that helped him reduce the impact of the incessant bullying (page 5):

One was his imaginary world of monsters and demons and apparitions. The other was an unexpected discovery – he found he had inherited something his grandfather’s character, and had a violent and absolutely ungovernable temper once he grew angry.

The latter characteristic posed a problem for Shelley though (ibid.):

All his life, Shelley was to detest violence and the various forms of ‘tyranny’ which it produced. Yet the exceptional violence in his own character, the viciousness with which he reacted to opposition, was something he found difficult to accept about himself.

There are no reminiscences recorded by either of his parents about Shelley: all we know is that, as a child, he found his mother (page 11) ‘increasingly distant and unresponsive, and there are indications that he felt deeply rejected.’ His later relationship with his father, after the age of 18, was extremely fractious. He (page 12) ‘dramatised him as the worst kind of tyrant and hypocrite.’

While Holmes warns us to treat these ‘melodramatic’ descriptions with caution, they are very revealing about Shelley’s ‘mythopoeic faculty,’ a major factor in his later creativity. Later (page 105) Holmes indicates, in the accounts Shelley gave of his childhood, that he ‘could be very unscrupulous in adjusting the truth when the need arose,’ but that ‘it is difficult to tell how far Shelley really realised – or admitted to himself – what he was doing.’

My later reading about trauma, undertaken after I had finished this sequence, may shed further light on this. Allowing for a number of caveats, including the way his upbringing prior to boarding school had infused a degree of narcissistic entitlement into his character, it is possible that his fierce temper may be at least in part attributable to his schooling. Joy Schaverian, in her thought-provoking book Boarding School Syndrome, describes what she learnt from a patient she calls Theo, not his real name. Prior to therapy he had often withdrawn from his wife and family for reasons that were not clear to him. Only when he confronted an example of his own violence during his school days did he begin to realise more fully the dynamics of his withdrawal pattern (page 86):

He knew he could be meaner, and this became evident to him when a boy unfairly kicked him during a rugby match. The next time there was a scrum, he took the opportunity to hit that boy. This is depicted in the picture shown below. He was shocked by his own violence and deeply ashamed in telling this story. This brought to light another aspect of the rage of which he was so scared. Theo’s extreme self-control was mustered to keep this aspect of himself at bay. He was worried about how vengeful he had been on this occasion.

Schooldays

A school contemporary at Syon House described Shelley (page 13) as having ‘considerable political talent, accompanied by a violent and extremely excitable temper.’

Shelley was also fascinated by science (page 16) in a ‘speculative and imaginative’ fashion, though ‘more naturally inclined to the field of social sciences – sociology, psychology, even parapsychology – than the physical ones.’

On his return to Field Place, the home of his childhood, after two years at Syon House, we see an escalation in the problematic side of his character (page 17):

Shelley’s natural mischievousness had become more uncontrollable, his games and experiment more violent, and his authority over his sisters more domineering.

A streak of indifference to others’ feelings, even cruelty, became apparent:

Shelley suggested that he will be able to cure his [sister’s] chilblains by [a] method of electrification, but his sister’s ‘terror overwhelmed all other feelings’ and she complained to their parents. Shelley was required to desist.

At Oxford he was later to torment his scout’s son, who had learning disabilities, with the same threat of electrification. His time at Eton replicated his experiences at Syon House, if not worse (page 19) since ‘the bullying by his fellow pupils was extremely severe.’ His experiences with authority were stained with the same dye so that (page 20):

He remembered these first years at Eton with an intensity of loathing that affected many of his later attitudes towards organised authority and social conformism.

The paragraph that summarises the consequences of all this early trauma concludes (page 21):

Of the damage that the early Eton experience did to him, repeating and reinforcing the Syon House pattern and reaction, there can be little doubt. Fear of society en masse, fear of enforced solitude, fear of the violence within himself and from others, fear of withdrawal of love and acceptance, all these were implanted in the centre of his personality so that it became fundamentally unstable and highly volatile. Here seem to lie the sources of his compensatory qualities: his daring, his exhibitionism, his flamboyant generosity, his instinctive and demonstrative hatred of authority.

Briefly at Oxford

In his brief time at Oxford, before being sent down for publishing a pamphlet on atheism, he developed a close friendship with Thomas Jefferson Hogg, the co-author of the pamphlet. Hogg has much to say about his impressions of Shelley. There was much he could not explain (page 42):

The fascination with firearms was one of many elements in Shelley’s character which Hogg, a very down-to-earth personality despite all his masterly sarcasms, could never really account for. Another was Shelley’s almost maniac disregard, on certain occasions, for the commonplace decencies of normal public behaviour, as the time when he seized a baby out of his mother’s arms while crossing Magdalen Bridge and began earnestly to question it about the nature of its Platonic pre-existence so that he might prove a point in an argument he was having with Hogg concerning metempsychosis. A third, and even more significant facet, which Hogg all his life tended to discount as mere comic ‘fancy,’ was Shelley’s natural and sometimes overwhelming sense of the macabre.

He delighted in ‘ritual horror sessions’ throughout his life and they were a constant marker of ‘the darker side of Shelley’s personality’ (pages 260-61). It is hardly surprising then that the most famous novel his second wife, Mary, ever wrote was Frankenstein.

He was also prone (page 114) to ‘attacks of hysteria; at its most extreme this could involve a screaming fit and complete prostration, and he would have to be put to bed and nursed.’

When the relationship with his father was moving towards meltdown over Shelley’s unorthodox behaviour and atheistic views, their shared inability to empathise with each other sank their chances of reconciliation (page 59):

Shelley could see no more than theological hypocrisy and paternal treachery; while Timothy could see no more than a spoilt and overconfident son dragging the whole family into social disgrace. So they were content to wound each other in the dark.

Boris Karloff as the Monster (For source of image see link)

His Traits as an Adult

Empathy was never Shelley’s strong suit in his personal life in spite of his compassionate identification with the oppressed in the political sphere.

This lack was dramatically displayed in the tactless treatment of the Elizabeth Hitchener’s father: this lady was risking her good name by developing a close relationship with him as a married man of dubious reputation. In a letter responding to Mr Hitchener’s concerns, Shelley wrote (page 141):

‘What the world thinks of my actions ever has, & I trust ever will be a matter of complete indifference. Your daughter shares this sentiment with me, and we are both resolved to refer our actions to one tribunal only, that which Nature has implanted in us.’

Holmes’s comment says it all: ‘It was a lapse typical of Shelley, typical of his blind self-assertion and sudden explosions of high-mindedness.’ His subsequent behaviour towards her, as the relationship cooled on his side, indicated that he did not have the faintest idea about the damaging impact of all this on the life situation of a vulnerable woman of lower social status who had, up to that point, been establishing the viable foundation for a secure future. His conduct put this completely in jeopardy. I also recognise we are speaking of a nineteen-year-old youth – given the prominence of Isis/Daesh and the prevalence of narcissism, not a male age group renowned at present for its sensitivity and wisdom. However, Shelley’s conduct frequently placed him close to the extreme end of the inconsideration spectrum.

Holmes feels that the character of the monster in Mary’s Frankenstein was drawn in part from Shelley and that expressions such as (page 333) ‘ . . . misery made me a fiend. Make me happy and I shall again be virtuous,’ from the monster, capture something of his psychodynamics. Shelley himself wrote of the monster (page 334):

‘Treat a person ill and he will become wicked.’ . . . . ‘It is thus that too often in society those who are best qualified to be its benefactors and its ornaments are branded by some accident with scorn, and changed by neglect and solitude of heart into a scourge and a curse.’ Implicitly, Shelley accepted his own identification as Frankenstein’s monster.

It is important to balance this with the generosity of his eventual treatment of Claire Clairmont at the time she was pregnant with Byron’s daughter (page 343). He admittedly had, unusually for him, a strong and protective connection with her, whose exact basis is hard to disentangle. Fiona MacCarthy, in her 2002 biography of Byron, is very clear (page 297-98) that ‘despite their close interdependence there was no evidence of a sexual bond between Shelley and Claire.’ There may have been such a connection at a later date, but this has not been confirmed beyond all doubt. Nevertheless, throughout the remainder of his short life he put himself out and sacrificed much to support her in her difficulties.

Shelley’s relationship with Byron was made more complex by his need to act as Claire’s advocate with Byron in terms of the future of their daughter, Allegra. Even without that, as MacCarthy indicates in her biography of Byron (page 298), their relationship would always have been pulled in at least two directions:

They fascinated, maddened one another. Intellectually compatible they were yet poles apart, Byron upholding the traditional and factual bases of philosophical argument, Shelley pursuing the further reaches of the experimental and visionary.

It is also true that Byron found it helpful that there was someone else around whose behaviour was even more openly unconventional than his own.

As he grew older, though still only in his twenties which he never outgrew, his health was also becoming a problem. Holmes detects three aspects (page 143): ‘hysterical and nervous attacks after periods of great strain,’ symptoms of a chronic disease associated with his kidneys and bladder’ and an interconnected ‘psycho-somatic area.’

He was not completely blind to his socially destructive impulses but was rarely able to curb them. Commenting on a letter Shelley wrote to William Godwin, with whom his relationship was positive at that point, Holmes writes (page 145):

It was a warm and touching letter. In the intellectual presence of one he felt he could trust, Shelley’s sense of personal inadequacy is revealing. He was rarely able to admit his own impatience and his own bitterness of feeling; more usually he was ‘unimpeached and unimpeachable.’

Incidentally, as his closeness to Godwin increased so did his distance from Elizabeth Hitchener, a painful development for her given how costly her association with Shelley was proving: Holmes (page 175) feels his behaviour demonstrated ‘a certain callous indifference to those he has grown disenchanted with.’

Another developing friendship, this time with the satirically inclined Thomas Love Peacock, helped him begin to learn how to ‘mock his own enthusiasms’ (page 174).

There was then an incident in Tremadoc, whose exact details are difficult to disentangle. It involved gunfire at night and what seemed to Shelley and his immediate relations to be a politically motivated attempt upon his life by disaffected locals whom his behaviour had antagonised. This, combined with his reaction to the Ireland experience, meant (page 198) that ‘he never returned’ to ‘political activism again.’ From that point on ‘Shelley regarded himself as a mouthpiece rather than as an instrument for political change.’ In a famous later phrase, he became ‘the trumpet of a prophecy,’ but ‘not the sword.’

Later still there was possibly an even more critical event: the suicide of his first wife, Harriet, to which his own callous disregard for her had made a special contribution. Claire Clairmont, to whom Shelley was closer than to anyone else in the world at that point, wrote in a letter that (page 356) ‘Harriet’s suicide had a beneficial effect on Shelley – he became much less confident in himself and not so wild as he had been before.’ Holmes unpacks this by saying: ‘For Claire, it was Shelley’s recognition of his own degree of responsibility – a slow and painful recognition – which matured him.’

It was because of the pain Shelley was causing those close to him that the painter, Benjamin Robert Haydon, described Shelley (page 360) as ‘hypocritical’ for criticising Wordsworth for his indifference to the suffering of trout that had been caught. Haydon, after a bruising interaction as a Christian with Shelley’s militant atheism, found him proud, ‘domineering and insensitive.’ Hazlitt, for his part, felt he was (page 362) a ‘philosophic fanatic,’ and described him as a ‘man in knowledge, [but] a child of feeling.’

His Atheism

The issue of Shelley’s atheism may not be as straightforward as many, including Holmes, have liked to think.

I feel that he was probably not atheist in the sense that Dawkins uses the word. His prose, poetry and scribbled drafts are littered with such expressions (Ann Wroe’s Being Shelley page 157) as ‘One mind, the type of all . . .,’ ‘Great Spirit,’ ‘Immortal Deity/Whose throne is in the Heaven depth of Human thought,’ or, as I have just recently read in Epipsychidion, ‘The spirit of the worm beneath the sod/In love and worship, blends itself with God.’

In an address in 2008 on The Spiritual Foundation of Human Rights, Suheil Bushrui quotes from one of the best stanzas in Shelley’s uneven Adonais to prove he was a believer in the Absolute:

Each of the founders of the world’s religions has spoken of the Absolute, the one fountain of light and moral guidance, so eloquently expressed by Shelley in Adonais, his noble elegy written on the death of his fellow poet, John Keats:

‘The One remains, the many change and pass;

Heaven’s light forever shines, Earth’s shadows fly;

Life, like a dome of many-coloured glass,

Stains the white radiance of Eternity,

Until Death tramples it to fragments.’

I think we can be certain, though, that Shelley did not believe in the same God as his Christian contemporaries.

Perhaps the closest we can get is the description of his beliefs in Romanticism, edited by Duncan Wu (page 820):

In truth, Percy’s attitude to God was more complex than the word ‘atheist’ suggests. It is not surprising that the concept was inimical to someone so opposed to an established church not merely complicit, but deeply implicated, in the social and political oppression prevalent in England at the time. On the other hand, he was tremendously attracted to the pantheist life force of Tintern Abbey, and could not resist pleading the existence of a similar power in his poetry. However, he stopped well short of believing in a benevolent deity capable of intervening in human affairs. Much of his poetry tacitly accepts the existence of a superhuman ‘Power,’ but its moral character is not always clear. . . . He could also contemplate the possibility of the universe without a creator. If any phrase were used to encapsulate his position, it might be ‘awful doubt[1]’ – a feeling of awe for the power evident in the natural world, mixed with scepticism as to whether it reveals a divine presence.

We will complete this race through Shelley’s life tomorrow.

Footnote:

[1] Mont Blanc line 77.

Read Full Post »