At last we’ve arrived at the point where I try and pretend I’m ready to tackle R. S. Thomas’s poetry.

He represents a particular challenge – he very often combines a modernist verse form with a quasi mystical content. The latter draws me strongly in, whereas the former pushes me back. The absence of music doesn’t help.

My reason for attempting to rise to this challenge is because Thomas combines spiritual themes to some degree sometimes with scientific and artistic ones, something which obviously appeals to me given my star of truth lightbulb moment.

Deus Absconditus and Theodicy

The Long Healing prayer of Bahá’u’lláh contains words that capture this challenge: ‘I call on Thee O Manifest yet Hidden, O Unseen yet Renowned, O Onlooker sought by all!’

Wynn Thomas strongly emphasises that:[1] ‘Thomas’s great quarry was ever the deus absconditus to whom the mystics of the ages had paid their awed tribute.’

Interestingly, at the same time as he searched for connection with God, he was scourged by the problem of theodicy:[2]

Thomas was ever helpless to deny his nagging, underlying recognition of the cruelty of the laws governing the world of God’s creation.

He never shook off the problem:[3]

The problem of accounting for the overwhelming evidence of suffering in the world supposedly created by a God of love: it tormented R. S. Thomas his entire life.

In the end he had to resort to the same solution as I do:[4]

His strategy [in the end] was to foreground that very transcendent otherness of God, and to emphasise that when thus coolly view sub specie aeternitatis the otherwise vivid world of human experience faded into ephemeral, illusory importance. . . . [Also] language could at best be but a darkling glass that inevitably muddled understanding.

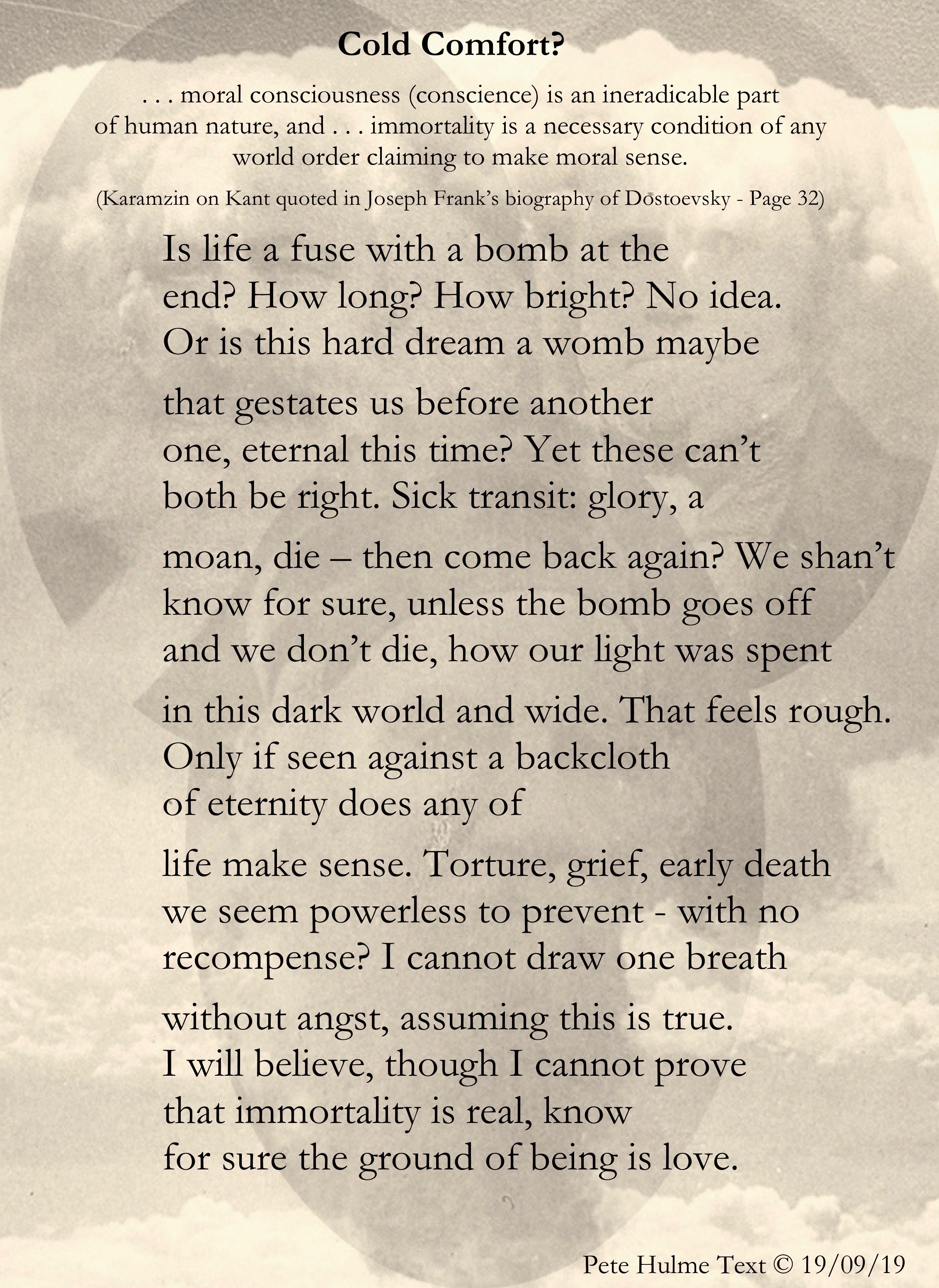

My poem is the closest I can get to capturing what this feels like.

Before we move on to Thomas’ more intermittent preoccupation with science and art, we need to look at a few examples of his poems about his struggle to connect with God. These are the ones that have most attracted me.

His consistent focus on this theme in his poetry came relatively late:[5]

[in 1972] recently settled in Aberdaron, despairing of both culture and politics,… he began to send out his distinctive verse probes into inner space.

. . . [Seamus Heaney in Stepping Stones says] ‘What I loved then were those later poems about language, about God withdrawn and consciousness like a tilted satellite dish – full of potential to broadcast and receive, but still not quite operating.’

Even though the theme draws me in, I need at the same time to confront the problem created by the absence of music and the pared back quality of his verse. Why wasn’t this enough to repel me from continuing to read him, as was the case with almost every other modernist poet?

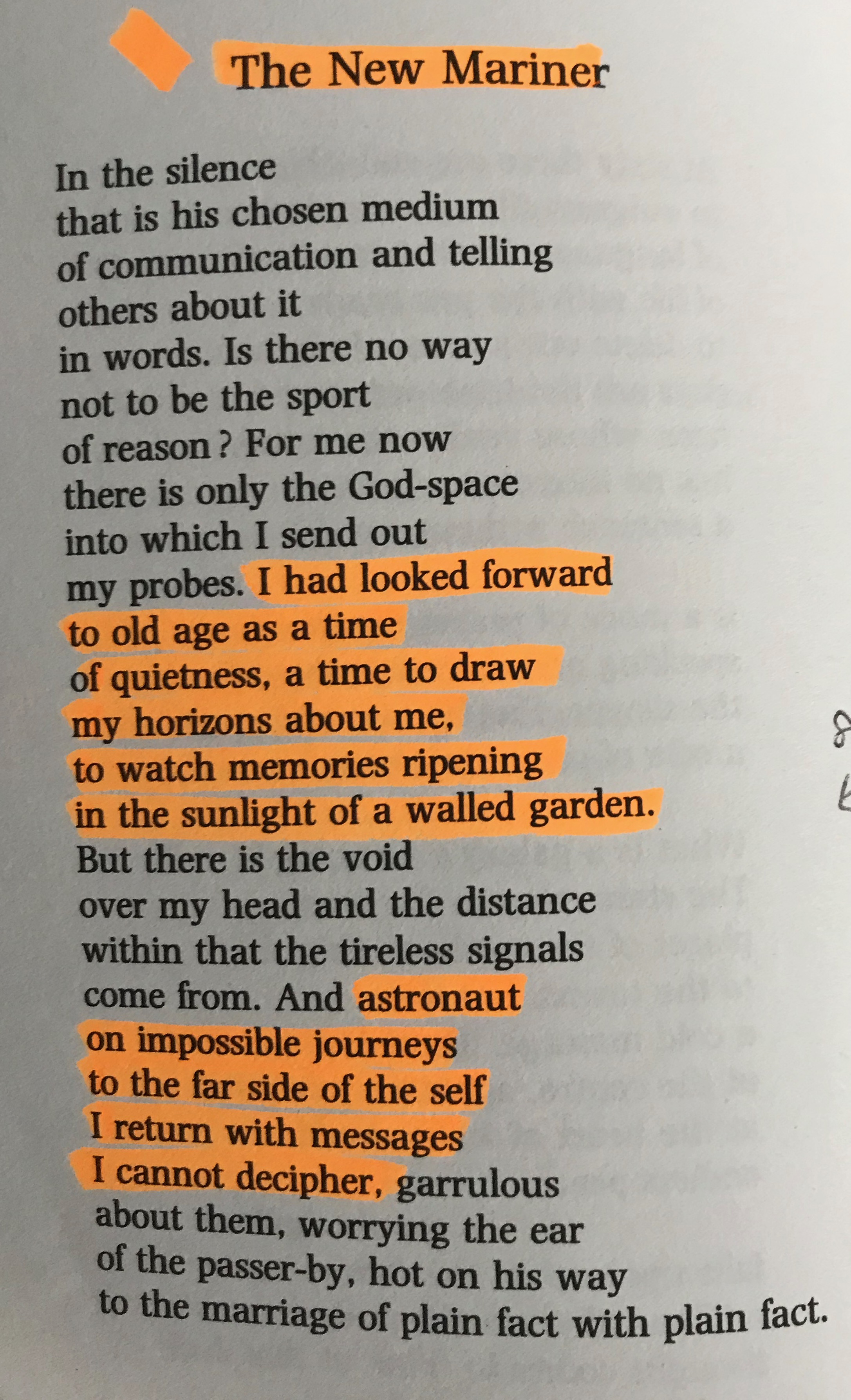

One of his poems to which I resonate most strongly is The New Mariner[6] which will hopefully go some way to giving a sense of where I’m coming from.

I suspect its resonance is partly because of the delightful self-mockery of the joking title and closing lines, and the memories they carry of Coleridge’s longer ballad, The Ancient Mariner. He speaks of returning from his ‘impossible journeys’ with ‘messages I cannot decipher’ and ‘worrying the ear/of the passer-by, hot on his way/to the marriage of plain fact with plain fact.’

The sarcastic metaphor describing the way he corners materialists who seek to sanctify their creed by marrying reductionist fact with reductionist fact exactly captures my own sense of naturalism’s defects which I try to convey on this blog and in conversation, ultimately based in my sense that matter is really not all there is. How could I not be drawn by the magnet of such poetry to keep revisiting it, in spite of the surface limitations that usually repel me?

The modernist manner is not cryptic or elitist. That helps. But there is more to the way he uses this style than that.

He has phrases that capture for me exactly the experience Thomas is seeking to convey. He describes ‘silence’ as God’s ‘chosen medium’ yet insists that he is ‘telling/others about it in words.’ The short and broken lines within which these phrases are embedded show us what a struggle it is for him. He doesn’t have to spell it out: he creates an experience that conveys it. The modernist style in fact helps him convey what he is seeking to express.

Even if I didn’t share that sense of his skill, the content would probably be enough to keep me engaged. Much of what I try to write in verse involves attempting to capture the inexpressible. The silence of the ground of being has always teased and tormented me.

The phrase ‘God-space’ into which he sends out his ‘probes’ implies exactly the kind of unresponsive infinity that resonates with my idea of an elusive universal mind with which it is virtually impossible to consciously connect.

He had hoped, as I did, that advancing age would probably correlate with increasing restorative quietness, ‘a time to draw/my horizons about me.’ No such luck. Rather than watching ‘memories ripening/in the sunlight of a walled garden’ such as my wife and I find at Berrington Hall, he suffers with ‘the void/over my head and the distance/within that the tireless signals/come from.’

Which contains another deeply resonant idea for me.

The Universe Within

Anjam Khursheed, in his book The Universe Within,[7] summarises our situation: ‘Humanity stands on the dividing line between two universes: the conscious universe within us and the external universe that surrounds us.’

Anjam Khursheed, in his book The Universe Within,[7] summarises our situation: ‘Humanity stands on the dividing line between two universes: the conscious universe within us and the external universe that surrounds us.’

Such attempts to capture what I have come to call the inscape, a term borrowed from Hopkins, have always fascinated me, not least because of the quotation from Ali, the successor of Muhammad in Bahá’u’lláh’s The Seven Valleys. In the earliest version I came across it reads:[8] ‘Dost thou reckon thyself only a puny form/When within thee the universe is folded?’ Anjam Khursheed in his book The Universe Within uses[9] almost identical wording from The Writings of Bahá’u’lláh[10] along with quotations from other religious traditions, to give warrant to the title of his book.

Khursheed raises an important point here:[11]

Our spirit of exploration and discovery in the external universe is not matched by a corresponding spirit for the inner universe. We are more comfortable conquering far away moons then exploring inner space.

Much as we might brag about[12] ‘the impressive gains in our knowledge of the external world, our knowledge of ourselves remains limited.’ We are essentially missing the point according to Laszlo:[13] ‘The critical but as yet generally unrecognised issue confronting mankind is that its truly decisive limits are inner, not outer.’

The initial trigger of my attraction to Thomas’ poetry came from his poem on this very theme – Groping [14]– where he writes ‘The best journey to make/is inward. It is the interior/that calls.’

Poetics

Wynn Thomas manages to explain in a partially convincing way how Thomas’ poetics work, but unfortunately does not deal with either The New Mariner or Groping.

One example he uses from the Collected Later Poems page 33[15] is The Echoes Return Slow.

The wrong prayers for the right

reason? The flesh craves

what the intelligence

renounces. Concede

the Amens. With the end

nowhere, the travelling

all, how better to get

there than on one’s knees?

He comments:

The poem … is written in the language and grammar of actual existential experience, and gives us the self agonistes, through lines that seem to be bent and buckled at the right-hand margins by the pressure of feeling to which they are almost palpably subject. The curt phrases, like those in Emily Dickinson’s poems, belong to an urgently compressed and curtailed style of mental notation, the poetic equivalent of the stammered morse code of a mind in the midst of spiritual emergency.

I definitely could not have put it better myself.

Another example he uses is What One Receives from Living Close to a Lake[16] a poem ‘that concludes with the following passage:

a clearing and made the entangled

forest of forms and voices,

anxious intentions, urgent

memories: a deep, clear

breath to fill

the soul, an internal

gesture, arms

flung wide to echo

that mute generous outstretching

we call lake.

He explains its power:

The layout maps the movement of mind, the line-breaks repeatedly suggesting the brief searching for the right noun to follow the qualifying adjective (‘entangled’/’forest’, ‘urgent’/’memories’, ‘clear’/’breath’, ‘internal’/’gesture’), for the precise verb for its purpose (‘arms’/’flung wide’) for the object that exactly complements the verb (‘to fill’/’the soul’). The result is the conveying not of thoughts but rather of the act of concentrated thinking – in other words, of ‘contemplation’ sufficiently sustained so as to become ‘meditation’.

Art & Science

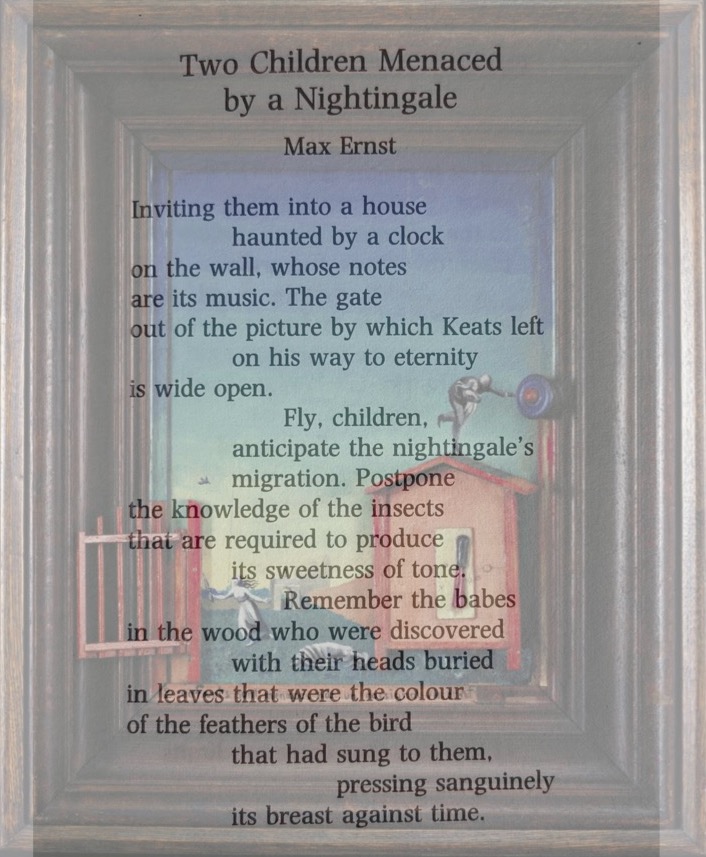

One poem I’ll focus on in a bit of detail, of the many in his Collected Poems: 1945-1990 which focus on works of art, is Two Children Menaced by a Nightingale.[17] Max Ernst is not the only surrealist Thomas addresses in his poetry – there are at least two poems triggered by the work of Magritte (see link for an example of a trigger painting). This one particularly attracted my attention because of its reference to Keats and obviously his Ode to a Nightingale.

According to the MOMA website Ernst described this work, made in 1924 – the year of Surrealism’s founding, as

“the last consequence of his [sic] early collages—and a kind of farewell to a technique…” He later gave two possible autobiographical references for the nightingale: the death of his sister in 1897, and a fevered hallucination he recalled in which the wood grain of a panel near his bed took on “successively the aspect of an eye, a nose, a bird’s head, a menacing nightingale, a spinning top, and so on.”

Without the picture I doubt whether I would have been able to even begin to make sense of the poem and vice versa. I’m still frankly puzzled by both the poem and the picture: that was probably the intention of both painter and poet!

What Thomas’ poem seems to be doing, which is worth drawing attention to, is using free association to shape his response to the painting, as though trying to beat Surrealism at its own game. He clearly draws in Keats given the strong association between Keats and nightingales, though Keats is clearly listening to the song in the dead of night rather than at dawn as the painting depicts, and also because the Ode addressing the nightingale flags up the power of poetry, albeit coloured by a longing for death in this context: ‘I will fly to thee . . . on the viewless wings of Poesy.’ It reminded me of the words of Bob Dylan – ‘Behind every beautiful thing there’s been some kind of pain’. Thomas fails to flag up the possibility that the gate does not only represent a possible escape for the children but is also perhaps inviting us to enter the picture and share the experience more closely.

He expands on the associations he has with nightingales beyond that to include migration and insects, implying, as a result, that the children’s flight could be some kind of migration from a hostile to a kinder climate, and suggesting that the children need to be shielded from the less pleasant habits of the nightingale than its song. His last association is to a sinister fairy tale, where the eventually dead children are covered in leaves by a robin not a nightingale.

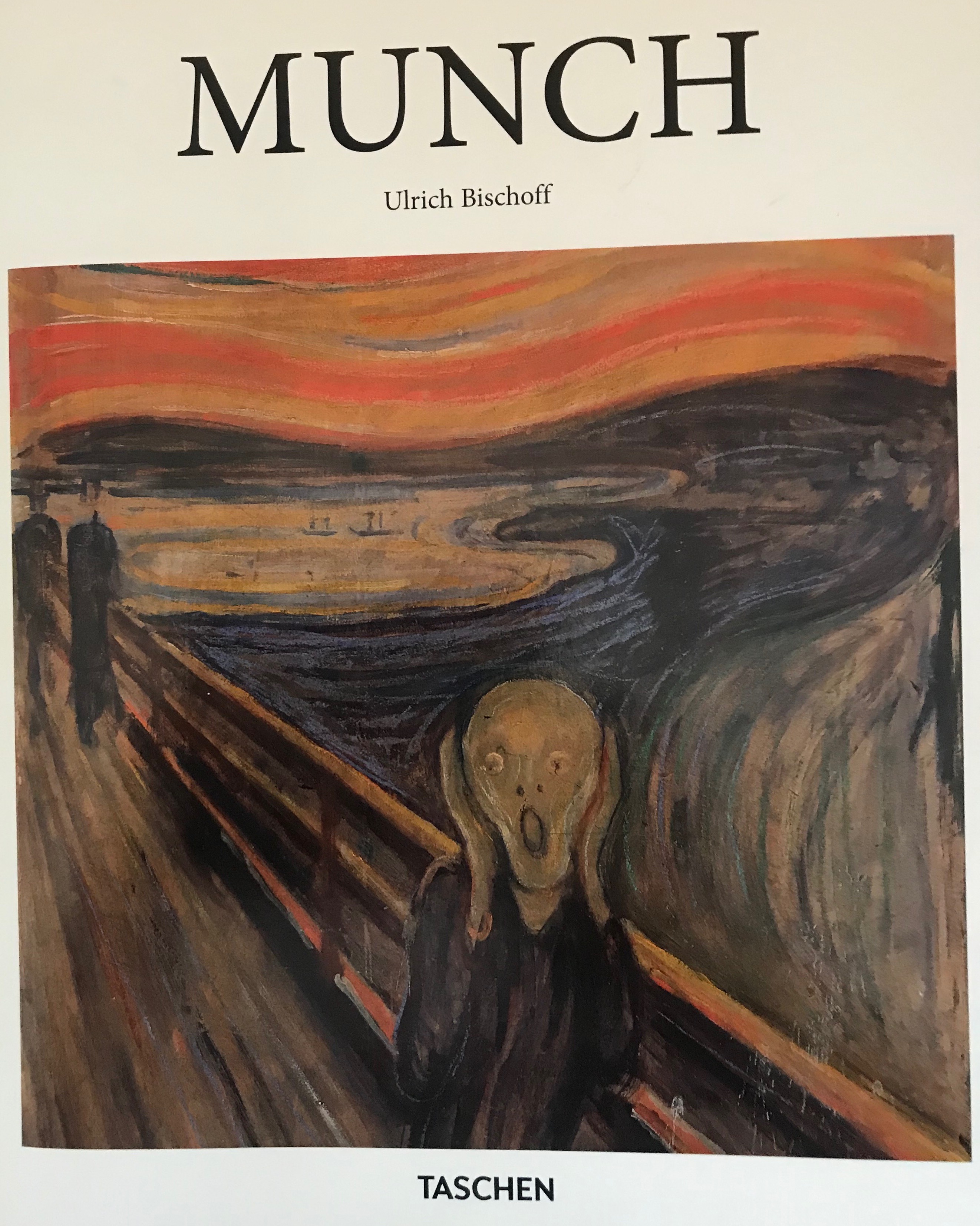

He may be also drawing associations into other poems such as Guernica[18] where the lines ‘The painter/has been down at the root/of the scream’ may be making a back reference to Munch’s painting The Scream, though there is also a scream clearly depicted in Picasso’s masterpiece. When I saw that painting full size in our visit to Barcelona I was blown away.

Interestingly, immediately preceding Guernica in the Collected Poems we find a reference to the possible close relationship for him of poetry and science. He writes[19] ‘Baudelaire’s grave/not too far/from the tree of science./Mine, too,/since I sought and failed/to steal from it…’

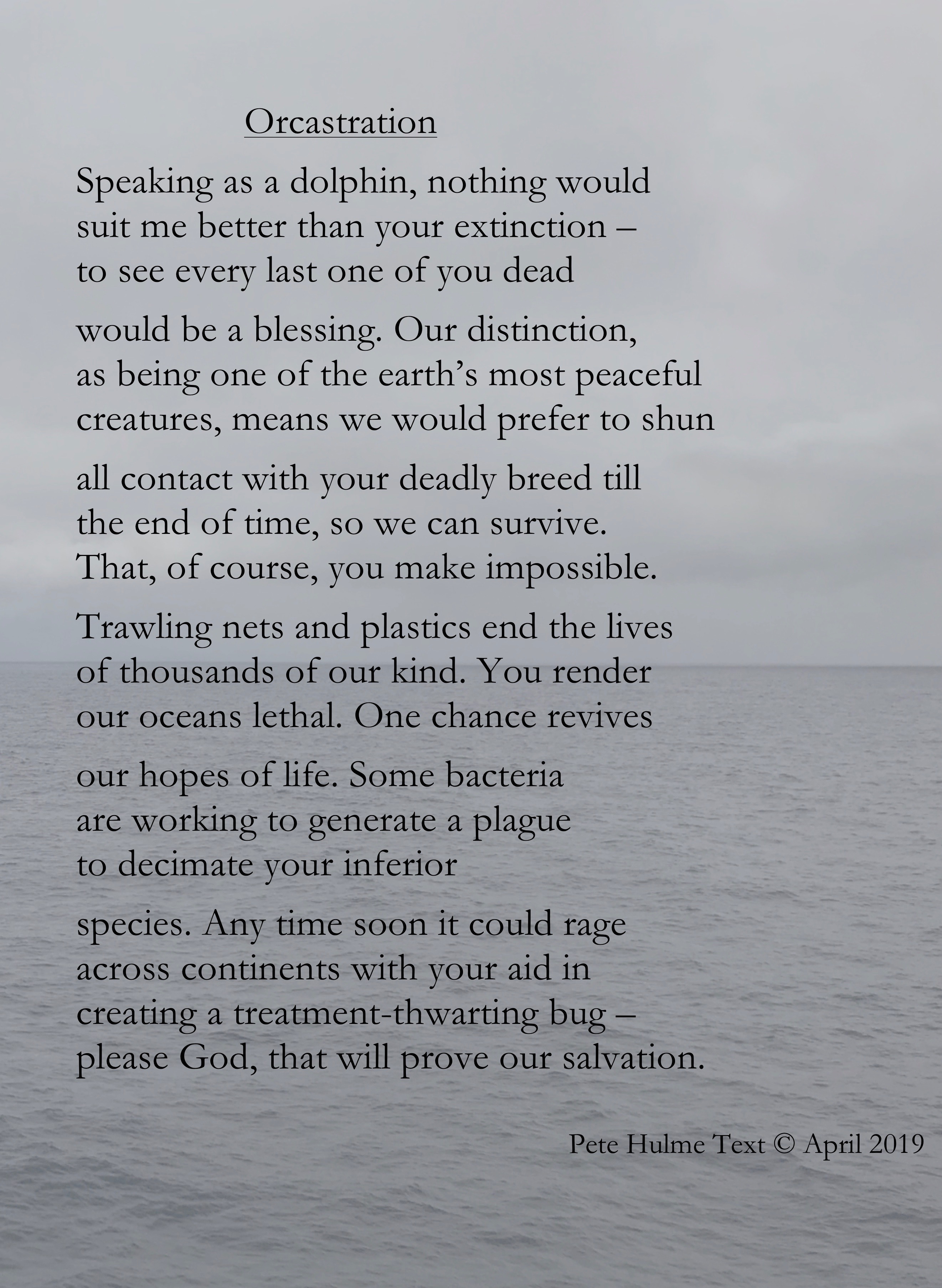

The New Mariner at the end makes clear his contempt for reductionist materialism but he is not blind to comparable defects in religion as practiced. He speaks[20] of the ‘human,/that alienating shadow/with the Bible under the one/arm and under the other/the bomb.’ He is also aware of our more mundane but none the less lethal destructiveness when technology shackles itself to capitalism:[21] ‘They cut down trees/to have room to make money.’ He describes the call of whales as ‘regret/for a world that has men/in it,’ of which I had no memory when I wrote my wordy poem, Orcastration, on the same theme.

The New Mariner at the end makes clear his contempt for reductionist materialism but he is not blind to comparable defects in religion as practiced. He speaks[20] of the ‘human,/that alienating shadow/with the Bible under the one/arm and under the other/the bomb.’ He is also aware of our more mundane but none the less lethal destructiveness when technology shackles itself to capitalism:[21] ‘They cut down trees/to have room to make money.’ He describes the call of whales as ‘regret/for a world that has men/in it,’ of which I had no memory when I wrote my wordy poem, Orcastration, on the same theme.

Even though these occasionally recurring themes around art and science do resonate to some degree with me, what really keeps drawing me back to his poems is his constant quest for a connection with an elusive God which is far more resonant. It’s the first time for me I have found poems whose bleak modernism perfectly expresses and conveys the poet’s experience in a way that is not dispiriting but rather inspiring, and for that I am truly grateful.

Even though these occasionally recurring themes around art and science do resonate to some degree with me, what really keeps drawing me back to his poems is his constant quest for a connection with an elusive God which is far more resonant. It’s the first time for me I have found poems whose bleak modernism perfectly expresses and conveys the poet’s experience in a way that is not dispiriting but rather inspiring, and for that I am truly grateful.

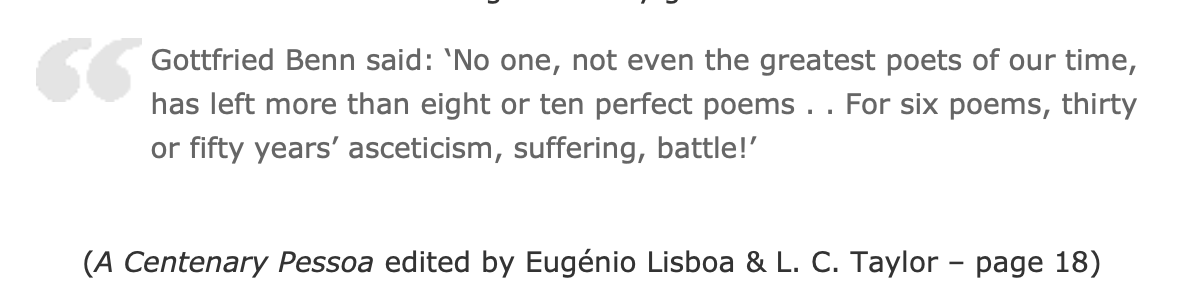

For me, it seems, the purpose of poetry is largely to capture deeply important but elusive experiences in words that will lift the understanding of every careful reader to a higher level. I have come to think that Thomas succeeds in doing so more often than most poets though not in every poem he wrote — but then no poet has ever succeeded in rising successfully to that impossible challenge, as a quotation I used in an earlier post makes clear:

Perhaps a fitting way to close this sequence is with the words of Wynn Thomas[22] which describe R. S. Thomas as ‘writing the modern history of a soul’ and goes on to say ‘This is the Thomas who seems to have fully discovered the natural idiom of his soul only late in his career, in his haunting religious poetry.’

References:

[1]. R. S. Thomas to Rowan Williams – page 205.

[2]. Op. cit – page 208.

[3]. Op. cit – page 210)

[4]. Op. cit – page 210)

[5]. Op. cit – page 212.

[6]. Collected Poems 1945-1990 – page 388.

[7]. The Universe Within – page 7.

[8]. The Seven Valleys (1945 edition) – page 34.

[9]. The Universe Within – page 23.

[10]. The Writings of Bahá’u’lláh – page 40.

[11]. The Universe Within – page 157.

[12]. Op. cit. – page 10.

[13]. Op. cit – page 133.

[14]. Collected Poems: 1945-1990 – page 328.

[15]. R. S. Thomas: The Serial Obsessive – page 207.

[16]. Op. cit – pages 259-60.

[17]. Collected Poems: 1945-1990 – page 445.

[18]. Op. cit. – page 437.

[19]. Op. cit. – page 436.

[20]. No Truce with the Furies – page 51.

[21]. Op. cit. – page 43.

[22]. R. S. Thomas: The Serial Obsessive – page 10.