Posted in Poems | Leave a Comment »

Posted in Autobiographical, Poems | Tagged Charles Dickens, death, poetry, reading | Leave a Comment »

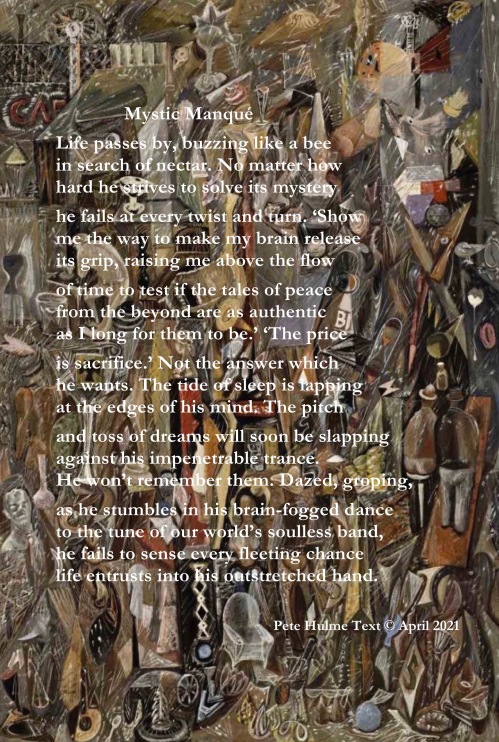

The picture is Rummage, 1941 by Mark Tobey (see Mark Tobey/Art and Belief by Arthur Dahl et al published by George Ronald for more information)

Given that the recent sequence on veils, words and values focused at some length on R. S. Thomas’s struggles to access God, reposting this poem that touches on a similar idea seemed worthwhile. My new poem posted last Monday was triggered by Thomas’s later poems.

Posted in Autobiographical, Poems | Tagged Art, brain, dreams, mysticism, poetry | Leave a Comment »

Given that the recent sequence on veils, words and values focused at some length on R. S. Thomas’s struggles to access God, reposting this poem that touches on a similar idea seemed worthwhile. My new poem posted last Monday was triggered by Thomas’s later poems.

The original Spanish is in the fourth post of the Machado sequence. For the source of the edited image, see link.

Posted in Poems | Tagged Antonio Machado, dreams, Edvard Munch, God, poetry | Leave a Comment »

Given that the recent sequence on veils, words and values focused at some length on R. S. Thomas’s struggles to access God, reposting this poem that touches on a similar idea seemed worthwhile. My new poem posted last Monday was triggered by Thomas’s later poems.

Posted in Poems | Tagged Fyodor Dostoevsky, immortality, Joseph Frank, poetry, reincarnation | Leave a Comment »

Given that the recent sequence on veils, words and values focused at some length on R. S. Thomas’s struggles to access God, reposting this poem that touches on a similar idea seemed worthwhile. My new poem posted last Monday was triggered by Thomas’s later poems.

Posted in Poems | Tagged appearances, chains, fear, interior, Meditation, pain, poetry | Leave a Comment »