Had the life and growth of the child in the womb been confined to that condition, then the existence of the child in the womb would have proved utterly abortive and unintelligible; as would the life of this world, were its deeds, actions and their results not to appear in the world to come.

(‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Bahá’í World Faith: page 393)

The theme of this much earlier sequence of posts seems to anticipate the next new post’s revisiting of the theme of theodicy, and therefore warrants republishing now.

In the previous two posts, I have been looking at Dabrowski’s Theory of Personal Disintegration (TPD) most particularly for what it has to say about suffering.

Both TPD and a rich and interesting approach to psychotherapy – Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) – owe much to existentialism. Mendaglio acknowledges his debt in the last chapter of the book he edited on this subject (page 251):

However, there is a great deal of similarity between existential psychology and the theory of positive disintegration. Both emphasise similar key concepts such as values, autonomy, authenticity, and existential emotions such as anxiety and depression. A more fundamental similarity is seen in the philosophical underpinnings of TPD, which is in large measure existentialism.

In spite of my own immense debt to existentialist thinking, only rivalled by my debts to Buddhism and to the Bahá’í Faith, I have certain reservations about Dabrowski’s take on the degree of choice we are able to exercise.

Crucial Caveats

His take on suffering is truly inspiring. Care needs to be taken though that we do not adopt this view in a way that assumes that those who are crushed by their sufferings are somehow to blame.

It is true that his model presupposes that each of us will probably meet a challenging choice point sometime in our lives, where we can either cling to the familiar comfortable half-truths that have failed us or strive to rise about them to higher levels of understanding. It is also true that he feels that many of us are capable of choosing the second option, if we only would.

However, not everyone is so lucky. I include here a brief summary of the life history of Ian – the man whose interview I have quoted extensively in the first three posts on An Approach to Psychosis.

His history shows very clearly that he could only make the second choice at times and then meet the pain and work through it to alleviate his tormenting voices. At other times the voices were preferable to experiencing the guilt and he chose what we might call madness rather than lucidity. Given the horrors he had faced it was clear that he should not be thought a failure. I would probably have done the same had I gone through what he had experienced in his life, from his earliest days.

Dabrowski seems to feel that our capacity to choose is genetically determined. Mendaglio explains (page 250):

Dabrowski . . . . postulated the existence of a third factor of development, representing a powerful autonomous inner force which is rooted in the biological endowment of individuals.

It seems to me that it would have taken a truly exceptional individual to make the choice to experience Ian’s level of pain in order to progress. If that does not seem quite convincing, there is another case history I would like to share very briefly.

Among the sequence of posts related to mental health there is a poem called ‘Voices.’ The woman upon whose experiences that poem is based, was brutally abused by her father, sexually, and by her mother, physically, from her earliest years through her mid-teens.

She came to us to work on her father’s abuse. We developed a safe way of working which involved starting with 15 minutes exploring how things had been since we last met. Then we moved on to 15-20 minutes of carefully calibrated work on the abuse. Then the last half hour of the session was spent helping her regain her ordinary state after mind after the work on her early experiences had intensified her hallucinations.

After almost a year of this work things seemed to be going well. Then came the unexpected. She found herself in a building that closely resembled the building strongly connected with the worst episode of abuse she had experienced at the hands of her father. Just being there was more than she could cope with. She became retraumatised in a way we none of us could have anticipated or prevented. The next time we met she could not stop sobbing.

We discussed what she might do. There were two main options.

She could, if she wished, continue on her current low levels of medication and move into a social services hostel where she would be well supported while we continued our work together, or she could be admitted onto the ward and given higher levels of medication in order to tranquillise her out of all awareness of her pain.

She chose the second option and I could not blame her in any way for doing so. It would be a betrayal of the word’s meaning to suppose she had any real choice at that point but to remain psychotic while the medication kicked in rather than deal with the toxic emotions in which she felt herself to be drowning.

It is when I consider these kinds of situation at my current level of understanding of his theory, that I feel it could leave the door open to destructive attitudes.

He believes, if I have understood him correctly, that some people’s genetic endowment is so robust they will ultimately choose the harder option regardless of the environment in which they grew up. Most of us are in the middle and with an environment that is not too extreme we will do quite well. The endowment of some is so poor, he seems to be saying, that it requires an optimal environment if they are to choose to grow even in a modest way.

This approach, if I have got it right, has two problems. The first, which is less central to the theme of this post, is that it is perhaps unduly deterministic because of the power that is given to inherited ‘endowment’ to determine the life course of any individual. The second problem is more relevant to current considerations in this post, though related to the first point. By placing such a determining role upon heredity, the force of the environment may be unduly discounted.

I am not claiming that he attaches no importance to environment. In fact, education for example is much emphasised in his work and he is clearly aware that limited societies will be limiting most people’s development – and he would include the greedy materialism of Western cultures in that equation. I’m not sure where he would place the impact of natural disasters in his scheme of things.

He may though be minimising the crushing impact of such experiences as the two people I worked with had undergone, in the second case throughout almost all her formative years. Could a strong genetic endowment have endured such hardship and come through significantly less damaged? If you feel so, you may end up not so much thinking ‘There, but for the grace of God, go I!’ but more ‘They broke because they were weak.’ Empathy, which Dobrawski values so much, would be impaired because we can start to define people as essentially different from us, not quite part of the same superior species.

More Complexities

This is a truly complex area to consider though, and I will have to restrict myself at this point to a very brief examination of one approach to it which does justice to that complexity.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá, in his description of the various components of our character, suggests that what we inherit is a source of either strength or weakness (Some Answered Questions: page 213):

The variety of inherited qualities comes from strength and weakness of constitution—that is to say, when the two parents are weak, the children will be weak; if they are strong, the children will be robust. . . . . . For example, you see that children born from a weak and feeble father and mother will naturally have a feeble constitution and weak nerves; they will be afflicted and will have neither patience, nor endurance, nor resolution, nor perseverance, and will be hasty; for the children inherit the weakness and debility of their parents.

However, this is not quite the end of the matter. He does not conclude from this that moral qualities, good or bad, stem directly from the inherited temperament of an individual (pages 214-215):

But this is not so, for capacity is of two kinds: natural capacity and acquired capacity. The first, which is the creation of God, is purely good—in the creation of God there is no evil; but the acquired capacity has become the cause of the appearance of evil. For example, God has created all men in such a manner and has given them such a constitution and such capacities that they are benefited by sugar and honey and harmed and destroyed by poison. This nature and constitution is innate, and God has given it equally to all mankind. But man begins little by little to accustom himself to poison by taking a small quantity each day, and gradually increasing it, until he reaches such a point that he cannot live without a gram of opium every day. The natural capacities are thus completely perverted. Observe how much the natural capacity and constitution can be changed, until by different habits and training they become entirely perverted. One does not criticize vicious people because of their innate capacities and nature, but rather for their acquired capacities and nature.

Our habits and choices have a crucial part to play. Due weight though has also to be given to the power of upbringing and the environment (Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Sec. 95, pp. 124–25):

It is not, however, permissible to strike a child, or vilify him, for the child’s character will be totally perverted if he be subjected to blows or verbal abuse.

This theme is taken up most powerfully by the central body of the Bahá’í Faith ((Universal House of Justice: April 2000):

In the current state of society, children face a cruel fate. Millions and millions in country after country are dislocated socially. Children find themselves alienated by parents and other adults whether they live in conditions of wealth or poverty. This alienation has its roots in a selfishness that is born of materialism that is at the core of the godlessness seizing the hearts of people everywhere. The social dislocation of children in our time is a sure mark of a society in decline; this condition is not, however, confined to any race, class, nation or economic condition–it cuts across them all. It grieves our hearts to realise that in so many parts of the world children are employed as soldiers, exploited as labourers, sold into virtual slavery, forced into prostitution, made the objects of pornography, abandoned by parents centred on their own desires, and subjected to other forms of victimisation too numerous to mention. Many such horrors are inflicted by the parents themselves upon their own children. The spiritual and psychological damage defies estimation.

This position allows for the fact that we need to take responsibility for our own development while at the same time acknowledging that we may be too damaged by the ‘slings and arrows of outrageous’ upbringing to do so to any great extent without a huge amount of help from other people. And most of us are the other people who need to exert ourselves to protect all children and nurture every damaged adult who crosses our path to the very best of our ability. Maybe Dabrowski is also saying this, but I haven’t read it yet. Even so his thought-provoking message is well worth studying.

In the end though, as the quote at the beginning of this post suggests, any consideration of suffering that fails to include a reality beyond the material leaves us appalled at what would seem the pointless horror of the pain humanity endures not only from nature but also from its own hands. I may have to come back to this topic yet again. (I did in fact return to a deeper consideration of Dabrowski’s model in a sequence of posts focused on Jenny Wade’s theory of human consciousness: see embedded links.)

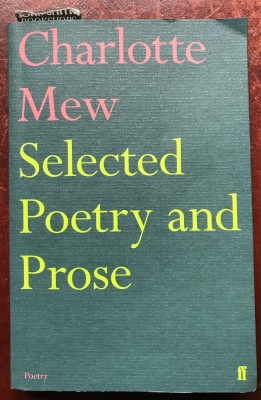

Given that my recent sequence includes references to the spiritual poetry of Táhirih, who wrote her mystical verse in 19th Century Persia, it seemed useful to republish this sequence on another woman poet. Though she was not a believer she struggled with deep spiritual issues in places.

Given that my recent sequence includes references to the spiritual poetry of Táhirih, who wrote her mystical verse in 19th Century Persia, it seemed useful to republish this sequence on another woman poet. Though she was not a believer she struggled with deep spiritual issues in places.  The poem is also is one of those that has the effect I described in an earlier post. I read these words from Madeleine in Church to my wife in the All Saints café in Hereford city centre, a most appropriate location:

The poem is also is one of those that has the effect I described in an earlier post. I read these words from Madeleine in Church to my wife in the All Saints café in Hereford city centre, a most appropriate location: It’s almost impossible to pin down exactly why that should be, apart from the probability that those words echo a sense of unworthiness most of us share at one time or another.

It’s almost impossible to pin down exactly why that should be, apart from the probability that those words echo a sense of unworthiness most of us share at one time or another.  Madeleine in Church, more than any other single poem of Mew’s, illustrates the extent of my resonance with her poetry.

Madeleine in Church, more than any other single poem of Mew’s, illustrates the extent of my resonance with her poetry. securely more of the implications of this richly evocative poem. Suffice it to say that I feel its psychological, narrative, spiritual and empathic depths warrant the attention of every discerning reader of poetry, whether they agree with what Mew seems to be saying or not. It captures so many of the key challenges and heart aches of the human condition.

securely more of the implications of this richly evocative poem. Suffice it to say that I feel its psychological, narrative, spiritual and empathic depths warrant the attention of every discerning reader of poetry, whether they agree with what Mew seems to be saying or not. It captures so many of the key challenges and heart aches of the human condition.

It seemed logical to follow on from the republished

It seemed logical to follow on from the republished  The Mad Woman in the Attic

The Mad Woman in the Attic