Because the next posts in the sequence about The Waste Land will be looking in some detail at issues relating to madness and modernism, it seemed appropriate to republish this sequence yet again.

The previous post looked at the Grof’s account of Karen’s experience of a spiritual emergency and how it was dealt with. Now we need to look at some of the implications as well as other aspects of their approach.

The Context

I want to open this section with that part of Bahá’u’lláh’s Seven Valleys that has formed the focus of my morning meditations for the last few weeks. I have persisted so long in the hope that I will eventually understand it more fully. I believe that Shoghi Effendi, the great-grandson of Bahá’u’lláh and the one whom ‘Abdu’l-Bahá appointed as His successor, was of the opinion that one needed to read at least ten books by writers who were not Bahá’ís in order to have any hope of understanding a Bahá’í text fully. I may have conveniently chosen to believe that factoid in order to justify my own bookaholic tendencies.

Setting that aside for now, what matters at the moment are the resonances between the words of Bahá’u’lláh and the topic I am exploring more deeply here.

I have touched on how materialistic assumptions about reality will dismiss as rubbish or even pathologise phenomena their paradigm excludes from possibility.

Bahá’u’lláh directly addresses this point (page 33):

God, the Exalted, hath placed these signs in men, to the end that philosophers may not deny the mysteries of the life beyond nor belittle that which hath been promised them. For some hold to reason and deny whatever the reason comprehendeth not, and yet weak minds can never grasp the matters which we have related, but only the Supreme, Divine Intelligence can comprehend them:

How can feeble reason encompass the Qur’án,

Or the spider snare a phoenix in his web?

Our deification of reason has stripped the world we believe in of God and made it difficult, even impossible, in some cases for some people, to entertain the possibility that God in some form does exist, though that would not be as some white-bearded chariot-riding figure in the sky.

This is the Grofs take on this issue (page 247):

This is the Grofs take on this issue (page 247):

A system of thinking that deliberately discards everything that cannot be weighed and measured does not leave any opening for the recognition of creative cosmic intelligence, spiritual realities, or such entities as transpersonal experiences or the collective unconscious. . . . . . While they are clearly incompatible with traditional Newtonian-Cartesian thinking, they are actually in basic resonance with the revolutionary developments in various disciplines of modern science that are often referred to as the new paradigm.

This world-view seriously demeans us (page 248):

Human beings are described as material objects with Newtonian properties, more specifically as highly developed animals and thinking biological machines. . .

We have taken this model or simulation as the truth (ibid.):

In addition, the above description of the nature of reality and of human beings has in the past been generally seen not for what it is – a useful model organising the observations and knowledge available at a certain time in the history of science – but as a definitive and accurate description of reality itself. From a logical point of view, this would be considered a serious confusion of the ‘map’ with the ‘territory.’

This reductionist dogmatism has serious implications for psychosis (page 249):

Since the concept of objective reality and accurate reality testing are the key factors in determining whether the individual is mentally healthy, the scientific understanding of the nature of reality is absolutely critical in this regard. Therefore, any fundamental change in the scientific world-view has to have far-reaching consequences for the definition of psychosis.

A Holographic Approach

They contend that the paradigm is shifting (ibid.:)

. . . The physical universe has come to be viewed as a unified web of paradoxical, statistically determined events in which consciousness and creative intelligence play a critical role. . . This approach has become known as holographic because some of its remarkable features can be demonstrated with use of optical holograms as conceptual tools.

Their explanation of the holographic model is clear and straightforward (page 250):

The information in holographic systems is distributed in such a way that all of it is contained and available in each of its parts. . . .

It’s implications are profound:

If the individual and the brain are not isolated entities but integral parts of a universe with holographic properties – if they are in some way microcosms of a much larger system – then it is conceivable that they can have direct and immediate access to information outside themselves.

This resonates with what Bahá’u’lláh writes in the same section of the Seven Valleys:

Likewise, reflect upon the perfection of man’s creation, and that all these planes and states are folded up and hidden away within him.

Dost thou reckon thyself only a puny form

When within thee the universe is folded?

Then we must labor to destroy the animal condition, till the meaning of humanity shall come to light.

It is crucial for us all as well as for those labelled psychotic that we cease to reduce the mind to a machine. The Grofs spell out the implications for psychosis when we refuse to take the more transcendent perspective (page 252):

The discoveries of the last few decades strongly suggest that the psyche is not limited to postnatal biography and to the Freudian individual unconscious and confirm the perennial truth, found in many mystical traditions, that human beings might be commensurate with all there is. Transpersonal experiences and their extraordinary potential certainly attest to this fact.

. . . In traditional psychiatry, all holotropic experiences have been interpreted as pathological phenomena, in spite of the fact that the alleged disease process has never been identified; this reflects the fact that the old paradigm did not have an adequate explanation for these experiences and was not able to account for them in any other way.

Assuming that we do accept that possibility of a spiritual reality, what follows? They spell it out:

. . . . two important and frequently asked questions are how one can diagnose spiritual emergency and how it is possible to differentiate transformational crises from spiritual emergence and from mental illness.

This is only possible up to a point (page 253):

The psychological symptoms of… organic psychoses are clearly distinguishable from functional psychoses by means of psychiatric examination and psychological tests.

. . . . When the appropriate examinations and tests have excluded the possibility that the problem we are dealing with is organic in nature, the next task is to find out whether the client fits into the category of spiritual emergency – in other words, differentiate this state from functional psychoses. There is no way of establishing absolutely clear criteria for differentiation between spiritual emergency and psychosis or mental disease, since such terms themselves lack objective scientific validity. One should not confuse categories of this kind with such precisely defined disease entities as diabetes mellitus or pernicious anaemia. Functional psychoses are not diseases in a strictly medical sense and cannot be identified with the degree of accuracy that is required in medicine when establishing a differential diagnosis.

What they say next blends nicely with the points made in my recent posts about where the dubious basis of diagnosis takes us (page 256):

Since traditional psychiatry makes no distinction between psychotic reactions and mystical states, not the only crises of spiritual opening but also uncomplicated transpersonal experiences often receive a pathological label.

This has paved the way to dealing with their approach to intervention and their criteria for distinguishing spiritual emergencies that can be helped from other states.

Holotropic Breathwork

Before we look briefly at their attempt to create criteria by which we might distinguish spiritual from purely functional phenomena I want to look at their recommended method for helping people work through inner crises. This method applies what the non-organic origin. This technique they call Holotropic Breathwork.

First they define what they mean by holotropic (page 258):

We use the term holotropic in two different ways – the therapeutic technique we have developed and for the mode of consciousness it induces. The use of the word holotropic in relation to therapy suggests that the goal is to overcome inner fragmentation as well as the sense of separation between the individual and the environment. The relationship between wholeness and healing is reflected in the English language, since both words have the same root.

They then look at its components and their effects (page 259):

The reaction to [a] combination of accelerated reading, music, and introspective focus of attention varies from person to person. After a period of about fifteen minutes to half an hour, most of the participants show strong active response. Some experience a buildup of intense emotions, such as sadness, joy, anger, fear, or sexual arousal.

They feel that this approach unlocks blocks between our awareness and the contents of the unconscious:

. . . . It seems that the nonordinary state of consciousness induced by holotropic breathing is associated with biochemical changes in the brain that make it possible for the contents of the unconscious to surface, to be consciously experienced, and – if necessary – to be physically expressed. In our bodies and in our psyches we carry imprints of various traumatic events that we have not fully digested and assimilated psychologically. Holographic breathing makes them available, so that we can fully experience them and release the emotions that are associated with them.

As Fontana makes clear in his book Is there an Afterlife?, experience is the most compelling way to confirm the validity of a paradigm of reality, so my experience of continuous conscious breathing in the 70s and 80s gives me a strong sense that what the Grofs are saying about Holotropic Breathwork had validity. My experience in the mid-70s confirms the dramatic power of some of the possible effects: my experience in the mid-80s confirms their sense that the body stores memories to which breathwork can give access. I will not repeat these accounts in full as I have explored them elsewhere. I’ve consigned brief accounts to the footnotes.[1]

They go on to explain the possible advantages of Holotropic Breathwork over alternative therapies (pages 261-263):

The technique of Holotropic Breathwork is extremely simple in comparison with traditional forms of verbal psychotherapy, which emphasise the therapist’s understanding of the process, correct and properly timed interpretations, and work with transference . . . . It has a much less technical emphasis than many of the new experiential methods, such as Gestalt therapy, Rolfing, and bioenergetics. . . . . .

In the holotropic model, the client is seen as the real source of healing and is encouraged to realise that and to develop a sense of mastery and independence.

. . . . . In a certain sense, he or she is ultimately the only real expert because of his or her immediate access to the experiential process that provides all the clues.

Distinguishing Criteria

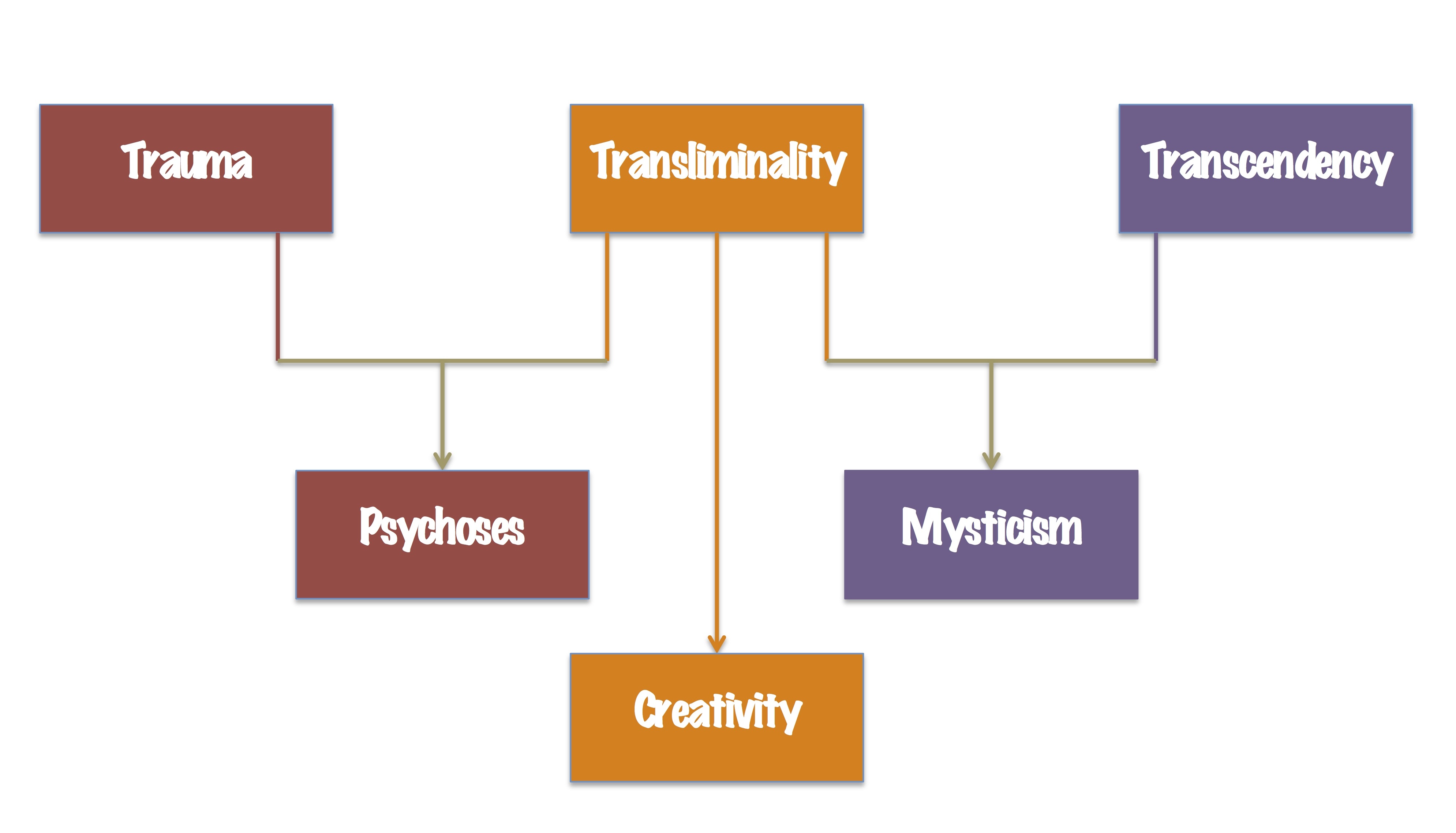

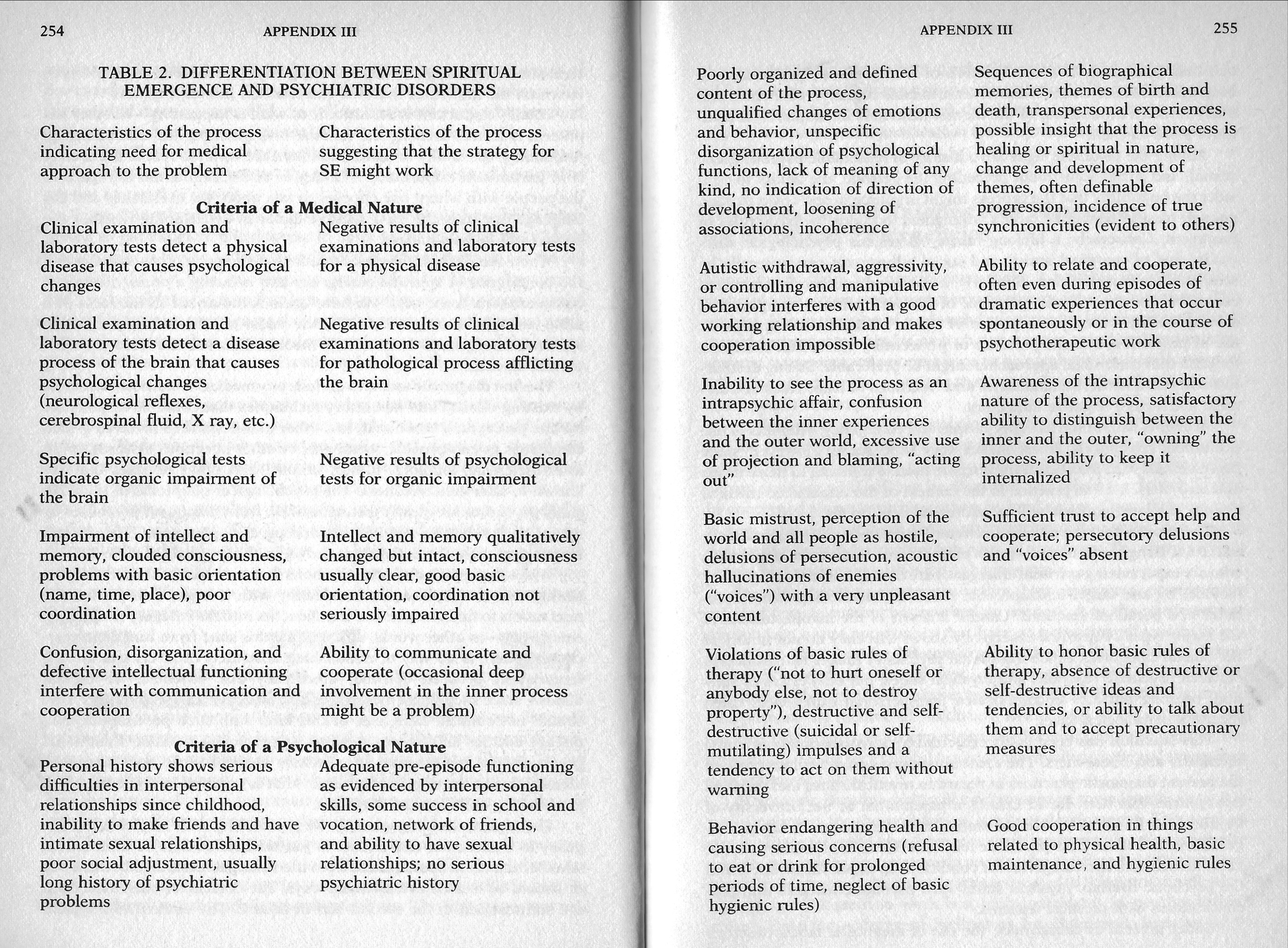

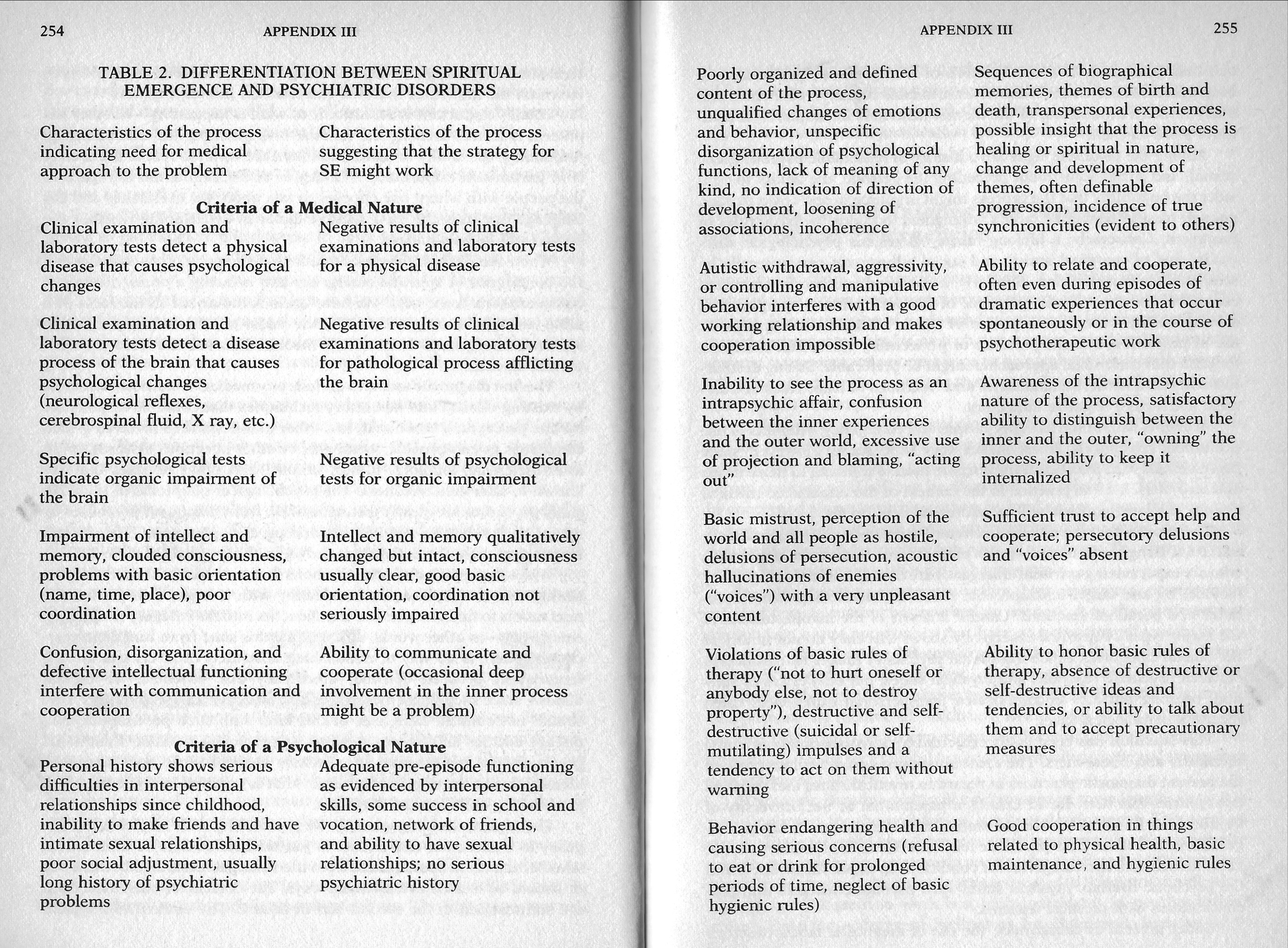

Below is the table they devised to differentiate between the two categories of spiritual emergence and what they term psychiatric disorder. They explain the purpose of the criteria (page 253):

The task of deciding whether we are dealing with a spiritual emergency in a particular case means in practical terms that we must assess whether the client could benefit from the strategies described in this book or should be treated in traditional ways. This is their table of criteria.

They are certainly not claiming that they have an unerring way of distinguishing between these states, nor that some of those who are placed in the ‘psychiatric’ have no aspects of spiritual emergency in the phenomena they are experiencing. Readers will also know by now that I am a strong advocate of more enlightened ways of managing any such problems than those which are implied in the term ‘traditional.’

Coda

This last post turned out to be much longer than I planned. I hope it conveys my sense of the value of their approach and of the validity of their concept of a spiritual emergency.

My feeling that their approach is a good one derives largely from my own dramatic experience of what was an almost identical method involving breathwork. In a previous sequence I have dealt with the way the breakthrough I experienced in the 70s had lasting beneficial effects on my my life, first of all in terms of opening my mind so I was able to take advantage of other therapeutic interventions. Perhaps most importantly though in the first instance was the way that the first breakthrough loosened the grip of my previous pattern of anaesthetising myself against earlier grief and pain mostly by cigarettes, gambling and heavy social drinking, so that I could realise that I needed to undertake more mindwork.

I also find it reinforcing of my trust in the basic validity of their perspective that it has led them to draw much the same conclusions as I have about the dangers of materialism and its negative impact upon the way we deal with mental health problems

It doesn’t end my quest though for more evidence to support my sense that psychosis can and often does have a spiritual dimension. Hopefully you will be hearing more on this.

Footnote:

[1] Rebirthing provided the experience that gave me my last major break-through in self-understanding by means of some form of psychotherapy. I heard first about it from a talk I attended on the subject at an alternative therapies fair in Malvern in early 1985. I then bought a book on the subject. The key was breathing:

Jim Leonard saw what the key elements were and refined them into the five elements theory.

The five elements are (1) breathing mechanics, (2) awareness in detail, (3) intentional relaxation, (4) embracing whatever arises, and (5) trusting intuition. These elements have been defined a little differently in several versions, but are similar in meaning. Jim Leonard found that if a person persists in the breathing mechanics, then he or she eventually integrates the suppressed emotion.

It was as though what is known as body scanning were linked to a continuous conscious breathing form of meditation. All the subsequent steps (2-5) took place in the context of the breathing.

After three hours I was trembling all over. I was resisting letting go and ‘embracing’ the experience. When I eventually did the quaking literally dissolved in an instant into a dazzling warmth that pervaded my whole body. I knew that I was in the hospital as a child of four, my parents nowhere to be seen, being held down by several adults and chloroformed for the second time in my short life, unable to prevent it – terrified and furious at the same time. I had always known that something like it happened. What was new was that I had vividly re-experienced the critical moment itself, the few seconds before I went unconscious. I remembered also what I had never got close to before, my feelings at the time, and even more than that I knew exactly what I had thought at the time as well.

I knew instantly that I had lost my faith in Christ, and therefore God – where was He right then? Nowhere. And they’d told me He would always look after me. I lost my faith in my family, especially my parents. Where were they? Nowhere to be seen. I obviously couldn’t rely on them. Then like a blaze of light from behind a cloud came the idea: ‘You’ve only yourself to rely on.’

The earlier experience had been more confusing, with no specific experience to explain it by.

Saturday was the day I dynamited my way into my basement. Suddenly, without any warning that I can remember, I was catapulted from my cushioned platform of bored breathing into the underground river of my tears – tears that I had never known existed.

It was an Emily Dickinson moment:

And then a Plank in Reason, broke,

And I dropped down, and down –

And hit a World, at every plunge, . . .

I’m just not as capable of conveying my experience in words as vividly as she did hers.

Drowning is probably the best word to describe how it felt. Yes, of course I could breath, but every breath plunged me deeper into the pain. Somehow I felt safe enough in that room full of unorthodox fellow travellers, pillow pounders and stretched out deep breathers alike, to continue exploring this bizarre dam-breaking flood of feeling, searching for what it meant.

Read Full Post »