. . . . the role of the fine arts in a divine civilization must be of a higher order than the mere giving of pleasure, for if such were their ultimate aim, how could they ‘result in advantage to man, . . . ensure his progress and elevate his rank.’

(Ludwig Tulman – Mirror of the Divine – pages 29-30)

Even though it’s barely a year since I last republished this sequence, its relevance to my sequence on Science, Spirituality and Civilisation is unmistakable. Art, as well as science and religion, has a role to play in understanding consciousness, so here it comes again!

A Test

As I explained earlier in this sequence, I’m not contending that mapping consciousness is the sole criterion for judging a work of art but it is a key one for my purposes as a student of consciousness, as the mind map above illustrates. I’ll unpack what the mind map is about later.

My ability to apply to ongoing experience what I have learned in theory was about to be tested. How clearly could I catch hold of and write down an experience under pressure?

The day I sat planning at some point to work on this post proved interesting. Two letters plopped through our letterbox. They looked like the ones I had been expecting, telling me when my next hospital appointments were.

I didn’t pick them up straightaway as I was keeping an eye on the pressure cooker as it built up a head of steam, ready to turn it down when the whistle hissed. No, I don’t mean my brain as it coped with all my deadlines. We were beginning to get the food ready for the celebration of the Bicentenary of the Birth of Bahá’u’lláh in two days time. The lentils apparently needed cooking well ahead of time.

Once pressure cooker duty was over, I dashed upstairs to tweak the slide presentation for the following day. I’d been enlisted to do the presentation at a friend’s celebration event. While the slide show notes were printing, I thought I’d better check the hospital letters out, not my favourite activity. The first one I opened was as I expected, an appointment for the ophthalmology department. I moved on to the second one. When I opened it I saw it was identical, same date, same time.

‘They’ve messed up,’ I groaned inwardly. ‘I was supposed to go for an MRI scan as well. I’d better give them a ring.’

I stapled the slide show notes together, picked up my iPhone and rang the number they had given me on the letter. A robot answered.

‘Thank you for calling the orthoptic department. We are currently dealing with a new electronic patient record system [I didn’t relish being seen as an electronic patient] and may be delayed in returning your call, [change of voice undermining the impression of caring that was to follow] but your call is important to us. Please leave your hospital number, the name of the patient, and a brief message and we’ll get back to you as soon as we can. Thank you.’

I responded after the beep, fortunately also remembering to give them my number as I wasn’t convinced they’d pick that up automatically. Most robots check whether they have absorbed your number correctly.

Rather than waste time waiting, I got my laptop and brought it downstairs to rehearse my presentation. I set up AppleTV and was just about to set my timer and start, when my phone rang.

‘Orthoptic Department. How can I help?’ She sounded pleasant and surprisingly unstressed.

‘The new system must be taking some of the pressure off,’ I thought.

I explained that not only had I got double vision but I was also now getting my letters twice as well. Well, no not really. I told her I’d got two identical letters when I’d expected one to be for an MRI scan.

She checked out what I meant and then explained that the letter I’d got was for my routine appointment. The other was an error on their part. I should also be getting a letter for the MRI scan, I clarifed, but they did not know anything about that. I added that after that I should get an appointment from a consultant about the scan. She couldn’t help with that either, even though he was in her department.

She agreed to put me through to discuss the MRI.

‘Radiology here. How can I help?’

‘Is that where you do MRI scans?’ I asked, not being sure whether they counted as radiology or something else.

‘Yes, it is.’

I began my explanation.

‘I’m sorry. I need your name and date of birth.’

‘Will my hospital number do?’

‘Yes. That’s fine.’

Once she knew who I was, I told her my problem and asked when I could expect my scan to be as were we hoping to be away some time in December.

‘It’ll take 6-8 weeks from the time they sent the request.’

‘So when might that be?’

‘It’ll probably be the week beginning 27 November.’

‘And when will the consultant see me to discuss it after that.’

‘I can’t say because he wouldn’t send out appointments normally until he receives the scan.’

‘So how long is the gap likely to be then?’

‘We don’t deal with that. You’d have to speak to his secretary.’

She couldn’t put me through so I rang Ophthalmology again and got the robot. I hung up and rang the hospital switchboard and they put me through straightaway. Must remember that next time.

I spoke to the same person as before. She explained that she didn’t really know. She was just the receptionist. His secretary was off till next week. She’d leave a note for her and if I could ring back then she might help.

I hung up and made a note in my diary to ring next week.

Before this all happened, I’d jotted down in the notebook I always carry: ‘It doesn’t matter whether I’m enjoying myself or not, as long as I’m squeezing every drop of meaning out of the lemon of the present moment.’ The phone calls to the hospital where a particularly sour experience, so my note was intriguingly prophetic. I had managed to stay calm, and even found the whole experience slightly amusing with its many examples of ‘I don’t know. That’s not my department. You need to talk to…’

At last I was able to settle down and rehearse the presentation before finally returning to my plan to draft this post.

The whole episode highlighted for me the need not only to slow down and keep calm, but also to sharpen my focus. Not that I will ever be able to write as well as Virginia Woolf, but without that combination of skills I doubt that anyone would ever be able to capture consciousness in words on paper, or even in speech.

So now we come back to the critical question. Is its skill in conveying consciousness a valid criterion by which to judge a work of art? As I indicated earlier, I’m not arguing it is the only one, nor even necessarily the best. What I have come to realise is that it is a key one for me.

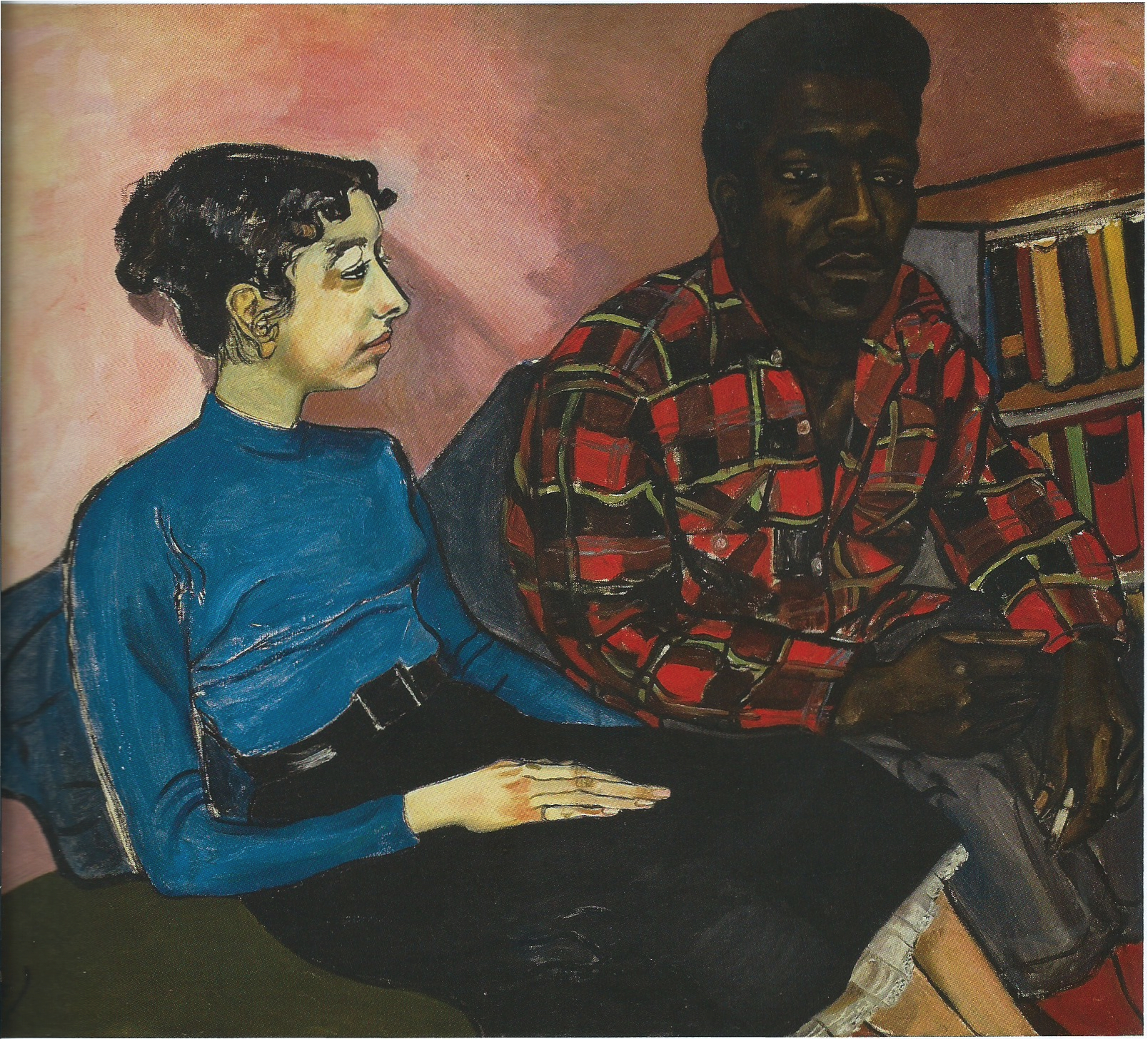

I also need to clarify that capturing consciousness is not the same as conveying a world view or meaning system. So, you might argue that when Alice Neel is painting people that the art world usually ignores, just as I gather Cézanne also did, while the act of painting itself is sending a clear ideological message that these people matter, unless the portrait is more than a realistic rendering of the subject’s appearance we have not been capturing the artist’s consciousness. If any distortions of sensory experience merely serve to strengthen the message, these would be more like propaganda than maps of consciousness. Also the culture in which we are immersed, as well as our upbringing and individual life experiences, influence the meaning systems we adopt, or perhaps more accurately are induced into evolving.

Capturing consciousness is also a tad more demanding than simply conveying a state of mind or feeling, whether that be the artist’s own or their subject’s, something which music can also do perfectly well. That is something I value very much, but it’s not my focus right now.

Taking that into account, what am I expecting?

Woolf gives us a clue in her diaries ((page 259):

I see there are four? dimensions: all to be produced, in human life: and that leads to a far richer grouping and proportion. I mean: I; and the not I; and the outer and the inner – … (18.11.35):

I have quoted this already in an earlier post of this sequence. I also added the date on which she wrote it to emphasise that it was after the completion of both To the Lighthouse and The Waves, as if she sensed that her approach up to that point had been too inward looking. Her question mark after ‘four’ suggests she was entertaining the possibility of more dimensions.

The diagram maps what Woolf said very crudely. Most of To the Lighthouse and The Waves takes place in the top right hand quadrant. They are brave experiments. In places they work beautifully but are uneven and at times disappointing. She sensed that I suspect.

The diagram maps what Woolf said very crudely. Most of To the Lighthouse and The Waves takes place in the top right hand quadrant. They are brave experiments. In places they work beautifully but are uneven and at times disappointing. She sensed that I suspect.

However, other novels she wrote take more account of the other quadrants except possibly the one on the bottom right, although there are places where she seems almost to be attempting to tune into the inscape of natural objects.

Clearly then it might be appropriate to judge a novel by how well it balances the three main quadrants, ie excepting the bottom right.

There is a catch here though. It all depends upon on what the prevailing culture defines as ‘outer.’ Is this to be confined only to the material realm? Mysticism is present in all cultures to some degree, though its legitimacy has been downgraded in the West. The critically endorsed novel has, with some rare exceptions such as John Cowper Powys and perhaps what is termed ‘magical realism,’ been seen as needing to focus on the world of the senses, the stream of consciousness and social interaction.

Is that enough?

Woolf expresses this whole dilemma with wry humour in To the Lighthouse (page 152):

Woolf expresses this whole dilemma with wry humour in To the Lighthouse (page 152):

The mystic, the visionary, walking the beach on a fine night, stirring a puddle, looking at a stone, asking themselves “What am I,” “What is this?” had suddenly an answer vouchsafed them: (they could not say what it was) so that they were warm in the frost and had comfort in the desert. But Mrs McNab continued to drink and gossip as before.

Should a work of art, could a work of art, express some kind of world consciousness, for example? Should mysticism be normalised and not be either excluded or presented as eccentric?

Given that I think expanding our consciousness is the key to enabling us to mend our world I am sceptical of any school of thought that would devalue and marginalise novels that attempt to treat outlying ways of thought and experience as of equal interest and legitimacy. It has already been demonstrated that the novel, in its present form, enhances empathy. It helps connect us in a more understanding way with the experiences of others very different from ourselves. Art in general is one of the most powerful means we have for lifting or debasing consciousness. It reaches more people in the West probably than religion does, especially if we include television, cinema, computer games etc.

I must add a word of warning here. Consciousness can be seen as expanding in all sorts of different ways.

Sometimes, though, I feel that just by pandering to our desire for exciting new experiences we might not be expanding our consciousness at all, but narrowing it rather.

Alex Danchev, in his biography of Cézanne, quotes an intriguing passage from Hyppolyte Taine (page 104):

Alex Danchev, in his biography of Cézanne, quotes an intriguing passage from Hyppolyte Taine (page 104):

In open country I would rather meet a sheep than a lion; behind the bars of a cage I would rather see a lion than a sheep. Art is exactly that sort of cage: by removing the terror, it preserves the interest. Hence, safely and painlessly, we may contemplate the glorious passions, the heartbreaks, the titanic struggles, all the sound and fury of human nature elevated by remorseless battles and unrestrained desires. . . . It takes us out of ourselves; we leave the commonplace in which we are mired by the weakness of our faculties and the timidity of their instincts.

I draw back instinctively from the elevation of the titanic, the fury, the remorseless and the unrestrained in human life. Exploring those aspects of our nature unbalanced by other more compassionate and humane considerations is potentially dangerous for reasons I have explored elsewhere. To express it as briefly as I can, it’s probably enough to say that I can’t shake off the influence of my formative years under the ominous shadow of the Second World War. I’m left with a powerful and indelible aversion to any warlike and violent kind of idealism, and any idolising of the heroic can seem far too close to that for comfort to me. Suzy Klein’s recent brilliant BBC series on Tunes for Tyrants: Music and Power explores what can happen when the arts are harnessed to violent ends in the name of some dictator’s idea of progress.

I am at a point where I have decided that I need to explore consciousness more consistently, perhaps more consistently than I have ever explored anything else in my life. It blends psychology, literature, faith as well as personal experience, and therefore makes use of most of my lifetime interests. This object of interest would give them a coherence they have so far lacked. Instead of flitting between them as though they had little real or deep connection, I could use them all as lenses of different kinds to focus on the one thing that fascinates me most.

I have ended up with the completely revised diagram of my priorities at the head of this post, repeated just to the left above in smaller size. The blurring at the edges represents its unfinished nature. It seems to express an interesting challenge. It shows that I am on a quest, still, to understand consciousness. Does the diagram suggest the idea that consciousness is both the driving force and destination of this quest? It looks as though consciousness is seeking to understand itself, in my case at least: that makes it both the archer and the target. Mmmmm! Not sure where that leads!

What is clear is that my mnemonic of the 3Rs needs expanding. It has to include a fourth R: relating. In the diagram I have spelt out what the key components are of each important R.

Relating

This involves consultation (something I have dwelt on at length elsewhere). It also entails opening up to a sense of the real interconnectedness of all forms of life, not just humanity as a whole. It has to entail some form of action as well, which I have labelled service, by which I mean seeking to take care of others.

Reflecting

How well a group can consult, as I have explained elsewhere, depends upon how well the individuals within it can reflect. My recent delving into Goleman and Davidson’s excellent book The Science of Meditation suggests that there is more than one form of meditation that would help me develop my reflective processes more efficiently (page 264): mindfulness I have tried to practice (see links for some examples), focusing I do everyday, using Alláh-u-Abhá as my mantra, and loving kindness or compassionate meditation is something I need to tackle, as it relates very much to becoming more motivated to act. I have baulked at it so far because it relies, as far as I can tell, upon being able to visualise, something I am not good at.

They also describe another pattern, which I’ve not been aware of before (ibid.): ‘Deconstructive. As with insight practice, these methods use self-observation to pierce the nature of experience. They include “non-dual” approaches that shift into a mode where ordinary cognition no longer dominates.’

Reading & Writing

Readers of this blog, or even just this sequence of posts, will be aware of how I use writing and reading in my quest for understanding so I don’t think I need to bang on about that here.

The Science of Meditation deals with the idea that long-term meditation turns transient states of mind into more permanent traits of character. I have placed altruism in the central space as for me, having read Matthieu Ricard’s book on the subject, altruism is compassion turned to trait: it is a disposition not a passing feeling. I am hopeful that insight may similarly turn to wisdom, but as I am not sure of that as yet, I just called it insight.

I am already aware that the diagram inadequately accounts for such things as the exact relationship between the 4Rs, understanding and effective and useful action. It does not emphasise enough that my desire to understand consciousness better is not purely academic. It is also fuelled by a strong desire to put what I have come to understand to good use.

I am also aware that I failed to register in my discussion as a whole that there are distinctions to be made between capturing consciousness in art and other closely related scenarios, such as describing experience in terms of its remembered emotional impact (conveying a state of mind) or giving an account of what happened through the lens of one’s meaning system (evaluating an event). It is perhaps also possible to attempt to convey only the basic details of what happened with all subjective elements removed (a ‘factual’ account).

I can’t take this exploration any further than this right now but hope to come back to the topic again soon. I also said in an earlier post that I might delve more deeply into the soul, mind, imagination issue. However, this post has gone on long enough, I think, so that will have to wait for another time.