Piazza del Duomo, Pisa (for source of image see link)

Whether we are considering greatness in art, or spirituality in human conduct, we need to remember that in both cases the light varies by degrees, and that even if it is brilliant, one can always aspire for it to become a bit brighter. This observation alone makes the argument of ‘good art despite bad conduct’ look suspicious, for in order to demonstrate the argument’s validity one has to state the criteria by which to distinguish between good and bad, and draw a line between the two.

(Mirror of the Divine: Art in the Bahá’í World Community by Ludwig Tuman – page 99)

As I’ll be launching soon into another exploration of the power of poetry, it seemed a good idea to republish one of my longest sequence of posts ever, which focuses positively on the power of art.

In the last post I quoted Hazlitt’s view from Holmes’s biography that Shelley was (page 362) a ‘philosophic fanatic.’ He described him as a ‘man in knowledge, [but] a child of feeling.’

Side Issue of Altruism

In the light of Hazlitt’s comment, it is perhaps worth mentioning here where all this maps onto my desire to understand more fully the influences that either strengthen or undermine altruism. Previous posts have examined how intense idealism creates a kind of empathic tunnel vision.

Shelley’s life poses an interesting question. In terms of his personal relationships the compass of his compassion was usually very narrow in its setting, and he often displayed a repellent inability to understand the suffering he caused. However, in terms of society it was set much wider – but there was a catch. Although nominally he strongly felt our common humanity should govern our relationships with one another, his powerful emotional identification with the oppressed, which possibly had its roots in his childhood mistreatment at the hands of authority in the public school system and the lack of protection from bullying by peers that went with it, meant that anyone he defined as an oppressor would be on the receiving end of his seething animosity and subject to remorseless duplicity.

One possible key to Shelley’s paradoxical stance of callousness to those in his immediate circle and compassion for the oppressed in general may have its roots in the trauma of his school days. Judith Herman, in her excellent treatment of this issue, Trauma & Recovery, describes something similar (page 56):

The contradictory nature of [one man’s] relationships is common to traumatised people. Because of the difficulty in modulating intense anger, survivors oscillate between uncontrolled expressions of rage and intolerance of aggression in any form. Thus, on the one hand, this man felt compassionate and protective towards others and could not stand the thought of anyone being harmed, while on the other hand, he was explosively angry and irritable towards his family. His own inconsistency was one of the sources of his torment.

When he fled into voluntary exile it is hard to determine the moral value of his flight. He feared imprisonment both because of his debts and because of his principles.

This indicates to me that unpicking the dynamics of altruism is not going to be easy. A facile attempt to distinguish between ‘cognitive’ and ‘affective’ altruism as a way of explaining political caring, on the one hand, co-existing in the same human being with personal callousness on the other, won’t get me very far.

Print of the Peterloo Massacre published by Richard Carlile (for source of image see link)

His Later Life

Enough of that for now.

After the death of their son, affectionately called Willmouse, Mary’s grief was great indeed. Shelley held himself back (page 520):

He decided that it was best to leave her to live out her own feelings and despair by herself. He continued his reading and writing through the summer… It was a harsh but characteristic commitment to his own craft.

It is in the period after the composition of Julian & Maddallo, a poem we will be looking at in a later post and which was unpublished at the time, that the vexed problem of the paternity of the child of their Swiss companion, Elise, further intensifies Shelley’s problems at this period of his life (pages 465-475). Holmes, after a detailed examination of the evidence concludes that the child was Shelley’s.

It is also possible that Claire miscarried at the same time as Elena was born, and that Shelley could also have been the father of that child, conceived at a later date. The evidence of both these possibilities is inconclusive, but the situation in his entourage was extremely fraught, not least because Clara, his infant daughter by Mary, died at this time. The circumstances that triggered her death were exacerbated by Shelley’s preoccupation with Elena’s birth and a mysterious illness of Claire’s.

Between 1818 and 1820 Shelley’s life had been extremely nomadic, involving ‘eight residences in rather less than twenty-four months’ (Holmes – page 575). He asks, ‘was Shelley running away from something, or was he running after something?’ Not an easy question to answer. Ann Wroe, in her book Being Shelley, shares one of his friend Hogg’s insights, along with a quote from Shelley himself (pages 170-71; the quote is from The Solitary in The Esdaile Notebook edited by K N Cameron):

As Hogg saw it, Shelley never fled towards, but escaped from, whatever it was that moved him. Shelley put it better: ‘He pants to reach what yet he seems to fly.’

It was in this period that his masterpiece of protest poetry was composed. The trigger for The Mask of Anarchy was what came to be known as the Peterloo Massacre which occurred at St Peter’s Field, Manchester, England, on 16 August 1819, when cavalry charged into a peaceful crowd of 60,000–80,000 that had gathered to demand the reform of parliamentary representation. There will be more of this when I come to consider his poetry in detail.

Others have achieved this in later times in song.

When he settled in Pisa in 1820 this restless pattern was cut across but not finally appeased, Holmes felt.

An important prose work in the Pisa period was his continuation of A Philosophical Review of Reform. It touched both on the role of poetry, a theme he returned to later as a separate issue, and on the nature of political process. He speaks (page 585) of the writer tuning in to ‘the spirit of the age’ and we first hear his concept of poets as ‘the unacknowledged legislators of the world.’

Concerning ‘the exploitation of labour through capital investment,’ Shelley influenced John Stuart Mill and Friedrich Engels (page 586). He saw the necessity for writers to raise the consciousness of not only the educated classes. He was also considering the issue of universal suffrage. He began to see the value of a ‘graduated response’ where small advances should not be rejected because a greater one was not currently practicable (page 590). If parliament drags its feet, he saw the value of ‘intellectual attack and a programme of public meetings and civil disobedience.’ He began to see passive resistance as a possible means of shifting the attitude of the soldiers who were acting as agents of the state in curbing protest (page 591). Holmes feels (page 592) that this document was a bold attempt ‘to define the relationship between imaginative literature and social and political change.’ It was not published for another 100 years. (This is not a record as a recent Guardian article indicates: see link).

Elena, his illegitimate daughter by Elise, died on 9 June 1820 though Shelley did not learn of it until early July (page 596), after his work on A Philosophical Review of Reform was completed.

Teresa, Contessa Guiccioli (for source of image see link)

Though Shelley was still producing poetry at this point, such as The Witch of Atlas and Swellfoot, the Tyrant, Holmes comments (page 612) on what he calls ‘a steady withdrawal of creative pressure and urgency,’ though his work as a translator continued to flourish.

One of the best descriptions of Shelley’s physical appearance and the impression he made late in life comes from Byron’s mistress at the time, Contessa Teresa Guiccioli. Fiona MacCarthy comments on and quotes her in her biography of Byron (pages 401-02):

She judged him as by no means so conventionally handsome as her own lover was. His smile was bad, his teeth misshapen and irregular, his skin covered with freckles, his unkempt hair already threaded through with premature silver. ‘He was very tall, but stooped so much that he seemed to be of ordinary height; and although his whole frame was very slight, his bones and knuckles were prominent and even knobbly.’ But Shelley still had a kind of beauty, ‘an expression that could almost be described as godly and austere.’

Thomas Medwin, on meeting him again after an interval of seven years, described him as ‘emaciated, and somewhat bent; owing to near-sightedness, and his being forced to lean over his books, with his eyes almost touching them; his hair, still profuse, and curling naturally, was partially interspersed with grey . . .’

Shelley’s health continued to be problematic, with painful attacks of what Medwin called ‘Nephritis’ (probably gallstones) which (page 618) caused Shelley to ‘roll on the floor in agony.’ Claire’s absence in Florence also saddened him. He missed her friendship and company.

He composed the Tower of Famine at this time and began an over-idealised relationship with Contessa Emilia Viviani (page 625), whose virtual incarceration in a convent while her parents sorted out a suitable marriage partner triggered most of Shelley’s romance electrodes, not least the combination of beauty and imprisonment.

At this time (page 626) he was also dabbling with mesmerism to ease his ‘nephritic spasms.’ It led him to speculate that, in mesmerism, ‘a separation from the mind and body took place – one being most active and the other an inert mass of matter.’ In Adonais, he was even tempted to explore the possibility of the immortality of the soul in the context of Something that looks remarkably close to an idea of God.

That Light whose smile kindles the Universe,

That Beauty in which all things work and move,

That Benediction which the eclipsing Curse

Of birth can quench not, that sustaining Love

Which through the web of being blindly wove

By man and beast and earth and air and sea,

Burns bright or dim, as each are mirrors of

The fire for which all thirst; now beams on me,

Consuming the last clouds of cold mortality.

Even so, any implications about the immortality of the soul would not, according to the critical consensus, have warranted a revision of his disbelief in God. My doubts about the possible simplifying myth of Shelley’s atheism are on the rise. It is as though emotionally he believed absolutely in the reality of transcendent forces to which he felt connected; intellectually he couldn’t allow himself to accept that this had anything to do with a god such as his contemporaries believed in. I find myself wondering whether in his poetry we will more consistently find belief, and in his prose more frequently a scathing scepticism: that’s something I might have to test out later.

Ann Wroe’s conclusion lends support to this possibility (page 353):

And early I had learned to scorn

The chains of clay that bound a soul

Panting to seize the wings of morn,

And where its vital fires were born

To soar . . . .Those lines, from 1812, were Shelley’s constant conviction as a poet. As a man, he was unsure . . . . .

She also reminds us of Shelley’s own explanation of his atheism (page 280):

When he redacted The Necessity of Atheism for his notes to Queen Mab in 1813, he added a new gloss to the words ‘There is no God:’ ‘This negation must be understood solely to affect a creative Deity. The hypothesis of a pervading Spirit co-eternal with the universe remains unshaken.’

Shelley, at this time and within a brief fortnight, wrote the 600 lines of Epipsychidion, (the title is Greek for ‘concerning or about a little soul’ from epi, ‘around’, and psychidion, ‘little soul,’ which Holmes (page 631) describes as an ‘extraordinary piece of autobiography’ and (page 632) ‘a retrospective review of his own emotional development since adolescence.’ In it he finds symbols (pages 635-636) to capture Shelley’s sense of Emily’s and Mary’s meaning in his life: Mary is the Moon, Emily the Sun while he is the Earth. He found a place for Claire also as a Comet!

Shelley’s own prose comment is illuminating (page 639), Epipsychidion:

. . . . is an idealised history of my life and feelings. I think one is always in love with something or other; the error, and I confess it is not easy for spirits cased in flesh and blood avoid it, consists in seeking an immortal image and likeness of what is perhaps eternal.

Next comes the composition of A Defence of Poetry. A brief consideration of this must wait till we come to the post on his poetry.

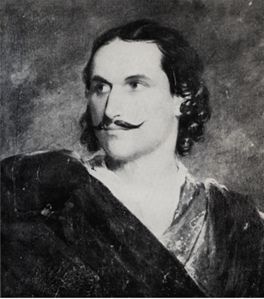

Edward John Trelawny (for source of image see link)

Three things mark this closing period of Shelley’s life. In terms of his relationships the death of Claire’s daughter, Allegra, of typhus fever in April 1822 is among the most important. In terms of the unexpected manner of his dying, he celebrated the arrival of his newly built sailing boat in May.

As for his poetry, he began composing The Triumph of Life. I may come back to that when I discuss his poetry.

In June he was bizarrely requesting his friend, Trelawny (page 725), for a lethal dose of ‘Prussic Acid or essential oil of bitter almonds[1].’

There is confusion in the end about the exact circumstances of Shelley’s death on his boat off the coast of Viareggio. MacCarthy agrees with Holmes that there was a squall. However, whereas Holmes paints a picture of Shelley’s almost suicidal recklessness as being the main cause of the vessel’s sinking, she feels there is the possibility that (page 428) ‘they were rammed and sunk by a marauding vessel.’

It is perhaps fitting that his death was as ambivalent as his life.

In the next post tomorrow I will be looking at the relationship between art and the artist in general terms. This will then lead to a set of posts reviewing Shelley’s poetry before I get round to trying to develop a tentative model of the creative process I can use to help me examine other artists’ lives – even so I’m possibly being slightly over-ambitious there, I think.

Footnote:

[1] Bitter almonds contain glycoside amygdalin. When eaten, glycoside amygdalin will turn into prussic acid, a.k.a. hydrogen cyanide.